Asian Americans need to speak out and stand up for themselves, psychologists say in panel.

By Ray Locker

Dr. Carolee Tran, a Vietnamese American psychologist practicing in Sacramento, Calif., was shopping in her local Costco when an older white man approached her in the aisle.

“You’re a disgusting, animal-eating Asian woman,” he said to her.

Tran, who was 8 years old when her family fled the collapse of South Vietnam in 1975, was not having it. “I said to him, ‘Shut the f— up, get out of my face or I am going to call the manager.’ I am sick of it.

“My daughter thought I was going to get killed,” Tran said.

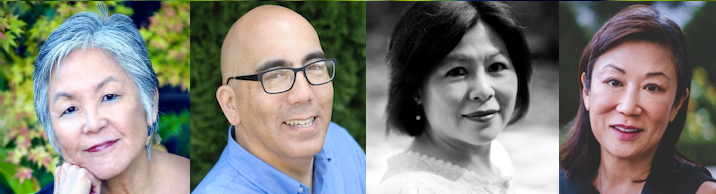

Program panelists included, from left, psychologists Satsuki Ina, Gordon Nagayama Hall, Carolee Tran and HMWF’s Shirley Ann Higuchi.

Tran, who joined psychologists Satsuki Ina and Gordon Nagayama Hall in a panel titled “Lessons From the Past: Yellow Peril in COVID-19 Times,” presented by the JACL on May 27 in conjunction with Asian American Heritage Month, said the time has come for Asian Americans to shed their historic reticence to speak up.

For too long, the panelists in the webinar, which was watched by more than 250 people, said that Asian Americans have tried to fit into the “model minority” niche consigned to them by white Americans; that provided comfort for many older people, particularly those who were among the 120,000 Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II.

Now, however, there is greater awareness that being a model minority is a myth that has stripped many Asian Americans of their identity and feelings of self-worth.

Ina, who born in the Japanese American concentration camp in Tule Lake, Calif., said for years she internalized the fears that surrounded her and her family after the incarceration. Her family was first sent to the camp in Topaz, Utah, and then to Tule Lake when they protested their treatment. After her birth, her father was sent to the prison in Bismarck, N.D., and then the family was sent together to Crystal City, Texas, where they were released in 1946, a year after the war ended.

“I had to rise above the legacy of fear they had lived through to find my voice,” said Ina, who is one of the founders of the social justice group Tsuru for Solidarity.

For most of her young life, Ina said, she followed the message that she had to be good and study hard. When most of her class of 100 students at the University of California, Berkeley, were out protesting, she was one of the two or three who showed up to class until her professor told her to get out with the rest of the class. “It kept me quiet for many years,” she said.

Now, however, as Ina witnesses the treatment of Latinx immigrants to the United States and the Trump administration’s family-separation policies, “I am pissed off and more activated than ever before.”

The webinar was moderated by Shirley Ann Higuchi, chair of the board of the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, a sponsor of the event, and the senior director for legal and regulatory affairs for the American Psychological Assn. Other sponsors were the National Council of Asian Pacific Americans, the Asian American Psychological Assn. and the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center.

Tran has captured the lessons she’s learned in a new book, “The Gifts of Adversity,” which recounts her journey from Vietnam to become the nation’s first Vietnamese American psychologist and her survival after suffering seven years of sexual abuse at the hands of a Roman Catholic priest. Higuchi is the author of an upcoming book that tells of her family’s experiences before, during and after the incarceration: “Setsuko’s Secret: Heart Mountain and the Legacy of the Japanese American Incarceration.”

Higuchi’s parents, William and Setsuko, were forced from their homes in San Jose and San Francisco and met as children in the seventh grade in the Heart Mountain school. They reunited as students at Berkeley and married in the 1950s.

Hall, who is a psychology professor at the University of Oregon, said Asian Americans face a constant stream of “microaggressions” from non-Asians, including questions about where they were really born or comments about how Asian American women are “exotic.” He cited a study that found that 78% of Asian Americans face some kind of microaggression every two weeks.

The son of a Japanese American woman who was incarcerated at the camp in Poston, Ariz., and a Caucasian man who served in the Navy during World War II, Hall said he learned that people “can be an ally even if they are not part of a group.”

His father, Charles Hall, grew up in Washington state, where he attended a Methodist church with a largely Japanese American congregation. When his father got leave during the war, he told his commanders he was visiting family members in Pennsylvania. Instead, he went to the camp in Heart Mountain, Wyo., where his friends from home were incarcerated.

“He stayed in the camp,” Hall said. “He did it because these people were his friends. He wasn’t trying to be noble.”

Second Class Petty Officer Charles Hall of Cold Bay, Alaska, is listed as a visitor in the Sept. 18, 1943, edition of the Heart Mountain Sentinel.

After the war, Charles Hall quit his local Elks Club when they refused to admit Japanese Americans and joined the Nisei Veterans Committee. “My dad became an honorary Nisei.”

That kind of bearing witness for others is critical to her current work with Tsuru for Solidarity, Ina said. That group fights to raise awareness of the treatment of Latinx immigrants and also organizes “healing circles” to help people cope with multigenerational mental health trauma.

Tran agreed. “We need to ally with other people about how this is a repeat of history,” she said. “We need to fight it with whatever we can. Every bystander needs to stand up.”