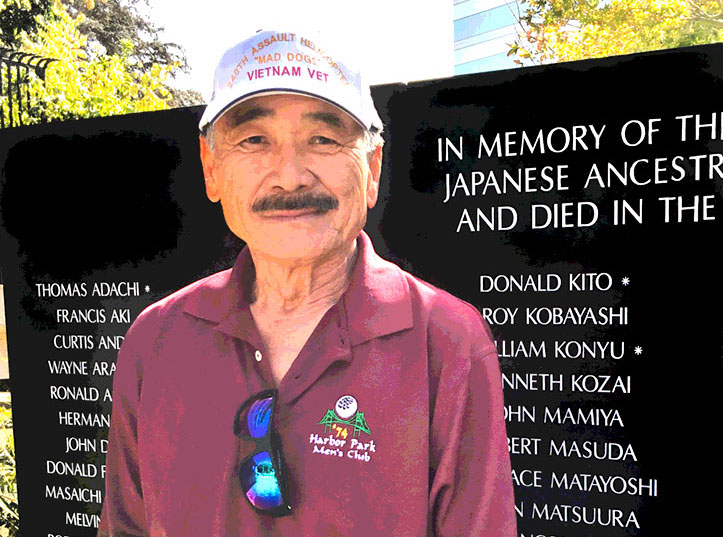

John Masaki stands in front of the Japanese American National War Memorial Court in Little Tokyo. (Pacific Citizen photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Five decades give Army veteran John Masaki the distance to reflect without regret.

By P.C. Staff

“It’s been 50 years.”

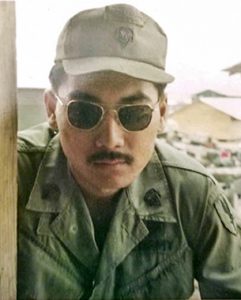

John Masaki, circa 1968-69 (Photo courtesy of John Masaki)

He says it matter-of-factly, but with a hint of incredulity in his voice. “I was there 50 years ago in ’Nam, in country, exactly 50 years ago. I was there at the beginning of September of ’68.”

For John Masaki of Lomita, Calif., the Vietnam War was long ago. Not counting time spent going through basic training and then the specialized training needed to serve in the Army as a door gunner and crew chief on a Bell UH-1C helicopter gunship, followed by a few months in North Carolina, his time as a G.I. “in country” was just a year — or “11 months and 29 days,” as he points out.

There is no denying, however, that that one year out of his 71 has had an outsized impact on Masaki’s life to this day — and will continue to, for the rest of it.

◊◊◊

Born in Torrance, Calif., in 1947, John Goro Masaki was, as his middle name reveals, the fifth Masaki child, the youngest among four boys, who, with three sisters, was one of seven Sansei children born to Haruko (née Fujikawa) and Setsuo Masaki.

Like many Japanese Americans of that era, the Masaki family were farmers, and families were larger than now, since more offspring meant free labor to supplement the braceros (seasonal farm workers from Mexico) they employed, which was how John picked up his nickname, Juan.

“My mother used to called me Juan until she passed away,” he said. “All the braceros called me Juan or Juanito. Didn’t bother me.”

Before World War II, “Sets,” as he was known to some and as “Jim” by other friends, and Haruko — who also went by Helen — farmed in Torrance, Calif., on the west side of Hawthorne Boulevard, near Del Amo Boulevard.

Their firstborn was daughter, Irene. Next came eldest son Victor, followed by James, then Richard, who died in 2014. John and his younger sisters, Aki (also known as Helen, who died in 2017), and Christine, were born after the family had returned to Los Angeles County, having been compelled by the U.S. government to leave their West Coast home like thousands of other U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry.

The Masaki’s would live in a horse stall at the Santa Anita racetrack in Arcadia, Calif., for six months before being moved yet again to be incarcerated at the War Relocation Authority Center in Rohwer, Ark.

The Masaki family was able to leave camp, however, when Sets found a sponsor in Brigham City, Utah, where he was hired to do farm work. He went first, and Haruko followed, kids in tow.

After the war ended, the family returned to Los Angeles County and resumed life as farmers. John was born in Torrance and grew up attending the same grammar school (now Madrona Elementary) from kindergarten through eighth grade.

Until the sixth grade, he was the only youngster who was Japanese, or Asian, for that matter, in his grade. In 1965, he graduated from high school, then worked for the family business while taking some classes at El Camino College.

“I wasn’t a very good student,” Masaki admitted. “I was kind of a screw-off.”

The same year John graduated, family patriarch Sets died at age 52.

“He was as healthy as a horse,” Masaki said. “It was an accident. He couldn’t swim a lick, and he died, drowning.”

The mid-1960s was also a time when the United States was escalating the war in Vietnam, and if you were a young man then, being drafted was a real possibility. For Masaki, that possibility became reality in 1967.

◊◊◊

As anyone who has watched episodes of TV’s “M*A*S*H” can attest, the military’s use of helicopters began in earnest during the Korean War. But it was during the Vietnam War when the aircraft came into its own, both as a weapon and a means to insert and extract troops, as well as carry the wounded to safety.

The Bell UH-1 Huey saw action in Vietnam as a flying gunship. (Photo: Lt. Col. S.F. Watson U.S. Army, NASM collection)

One could reasonably argue that the “Huey” — aka the Bell UH-1C Iroquois and its variants — is the symbolic visual shorthand for the Vietnam War, due to the Army’s extensive use of Hueys for all sorts of tasks, but especially as helicopter gunships.

According to Air & Space/Smithsonian magazine, “Between 1966 and 1971, one Army helicopter was lost for every 7.9 sorties — 564 pilots, 1,155 crewmen and 682 passengers were killed in accidents alone. More Hueys were downed in Vietnam than any other type of aircraft.”

A formidable weapon for the time, a Huey gunship was manned by two pilots and two door gunners, one of whom served as crew chief, who was responsible for the maintenance of his helicopter.

Each gunship was equipped with either two 19-pod rockets with no miniguns or seven-pod rockets with M134 miniguns. The two door gunners each operated an M60 machine gun, which was fed a belt of 7.62 mm cartridges and could fire at a rate of up to 700 rounds per minute.

When an M60’s barrel would inevitably get too hot, or worse, jam, the gunners would swap it out with the spare gun barrel they always made sure to have. While each gunner would also be equipped with an asbestos glove for handling a hot barrel, they were also issued M16s, which they would carry were there ever a need to exit the chopper if forced to land in a hot zone.

“It wasn’t my job, necessarily, to kill people,” Masaki said. “My job was to protect the aircraft as well as ourselves and all the other aircraft and troops.”

That also meant the door gunners used their M60s for suppressive fire to keep the enemy at bay as other helicopters delivered troops into a landing zone, or LZ.

But while killing the enemy may not have been the main objective, it surely could and did happen if a North Vietnamese soldier wasn’t smart enough to keep his head down as gunships unloaded a withering barrage of gunfire.

“Come on — if you’re going to fire a weapon at the enemy, don’t you mean to fire and kill them?” Masaki asked. “It’s a play on words, I suppose.”

◊◊◊

While three of the four Masaki brothers also served in the military, John was the only Masaki son to serve in Vietnam.

“My oldest brother never went in because he didn’t have to,” he said. “He was the brainiac of the family.”

Like many young men of draft age at that time, Masaki had mixed feelings about the Vietnam War, getting drafted, sent there and, possibly, maimed for life or killed.

“It’s the strangest thing as I think back when I was going there. I never once thought, ‘Bail out, Johnny-boy. Don’t go to ’Nam, what the hell for? A lot of people dying over there. What are we fighting for?’ ”

As to that last question, Masaki said he still doesn’t have an answer.

“To this day, I really don’t know,” he said, “other than the U.S of A. loves to promote its values on everybody else.”

Recalling his state of mind in the mid-1960s, Masaki said, “Mentally, I was just in limbo. Why would I want to go to Vietnam? Why would I even want to go in the Army if I don’t have to? I just kind of went along my daily functions of helping my family out, driving a truck for my dad’s business, going to El Camino to further my education.”

Then it happened. After getting his draft notice, Masaki got some advice from his older brother, James, who had already served in the military.

“When he knew I was going to get drafted, he said, ‘Let me give you some good advice. This is the best advice I could ever give you,’” Masaki remembered his older brother telling him. “‘Keep your nose clean. Don’t be an asshole.’”

James knew his younger brother sometimes seemed to have a chip on his shoulder, and in the Army, that meant trouble.

“Do as you’re told. All you’ve got to do is do what you’re told to the best of your ability,” Masaki remembered his brother telling him, giving him examples like spit-shining his shoes and cleaning brass with Brasso polish.

“If the sergeant tells you it’s not good enough, don’t give him shit. Continue till he’s happy with it,” James told him.

Masaki would, of course, have to undergo that rite of passage known to anyone who has ever served in the U.S. military: basic training. In September 1967, he reported to Fort Ord, Calif.

“It was a rude awakening,” he said, noting that he had never been away from home before.

While he wanted to adhere to his brother’s advice, Masaki recalled an incident during basic training at Fort Ord when he was assigned K.P. duty as a low-ranking E1.

A fellow G.I., who was a rank above him, told him,“Hey Jap, come over here. Clean out the grease pit.”

Although upset, he remembered his brother’s advice and remembered that he was supposed to follow orders, so he let it slide.

The next time Masaki had kitchen patrol, though, it happened again — and this time, Masaki let his Chicano tormenter have it.

When he got called in, he was asked by his company commander why he caused the fight. Masaki told him that it was the second time he had K.P. duty and the second time the other man called him a Jap.

“He called you what?” Masaki was asked. “A Jap,” he replied. “And I’ll knock the crap out of him if he does it again.” Masaki was dismissed.

The other G.I. never gave him a problem again and was busted down a stripe — and Masaki never had to do K.P. again. Still, he knew he screwed up.

“I didn’t need to fight him,” he admitted. It was a close call and a lesson learned.

◊◊◊

John Masaki’s cap tells the tale of his service during the Vietnam War. (Pacific Citizen photo: George Toshio Johnston)

After basic, Masaki was sent to Fort Rucker, Ala., for helicopter maintenance school. He remembers becoming pals with a fellow named Carlos Rodriguez, a Puerto Rican from New York, upon learning that he, too, would eventually be assigned to the 240th Assault Helicopter Co. for helicopter maintenance school.

“How the hell did I get into this to begin with?” Masaki remembers thinking at the time. “I have no idea. What do I know about helicopters? Zero. So, they taught us.”

After graduating, the next class was door gunner school, then crew chief school. His MOS (military occupational specialty) code was 67A10, then 67N20.

After completing his training, it appeared everybody would remain stateside and not go to Vietnam. Masaki would be stationed in North Carolina for the next few months.

“It was almost disappointing, which was kind of stupid,” he laughed. “They build you up to the point where that’s all you’re thinking about.”

North Carolina, as it turned out, was only temporary. Going to Vietnam was definitely in Masaki’s future — and it would definitely change him.

◊◊◊

Masaki said he has never been ashamed of having served in Vietnam, yet he allowed that “you do stuff over there that you’re not necessarily proud of.”

He remembers for instance, being on the lead gunship among four accompanying 10 troop carriers headed to an LZ, with a command aircraft safely above the fray at 3,000 feet.

Over the radio came the message that “we need to clean out our guns. Come in full suppression, fire away.”

Masaki was happy to comply — for about 10 seconds, until an urgent “Cease fire!” order was given.

The suppressive fire ended, and they continued the mission to deliver the troops. Then they got the news that they had inadvertently fired upon U.S. troops. While it wasn’t their fault, Masaki had to ask: “Were they on the left or on the right?” No one was sure. “Could it have been me?” he wondered. It might have been. Or not. To this day, Masaki doesn’t know.

There was another incident that has stayed with Masaki, in which he was given conflicting orders for what could have resulted in a court martial, and in this case, there was no doubt it was he who pulled the trigger.

Masaki recalled as they came upon an LZ, he reported via radio that he had “spotted a runner.” The gunship captain said, “Hang on” — but the command aircraft ordered, “Take him out.” With his target moving quickly, Masaki chose to follow the orders from above and unloaded, killing the target — who it turned out was a noncombatant. He was threatened with a court martial. Masaki said he was “shaking in my boots.”

However, the situation calmed down, and he never heard about it again. But Masaki says the memory of that disturbing, tragic incident has stayed with him ever since.

◊◊◊

After leaving the Army, Masaki had to deal with what a lot of veterans did and still do — return to civilian life, which for him meant driving for the family’s trucking business hauling strawberries and going back to school. As one might imagine, there’s not much work in the civilian world for a helicopter door gunner.

He had entertained thoughts of re-enlisting.

“When I got out of the service, I was kind of lost,” he said. “I thought, ‘Oh my. What am I going to do now?’

“My first thought was, ‘Boy, I’d sure like to learn how to fly a helicopter,” he continued. “I’d like to be a pilot.’ ”

Masaki said he could have easily reupped, gone to warrant officer training school and, thanks to his experience, qualified. What stopped him from taking that course of action was that he might have to return to Vietnam to pilot a medevac chopper or a slick, neither of which appealed to him.

A slick was a helicopter with no external weapon systems used to transport troops to landing zones, where the likelihood of getting shot at or shot down was much higher than being in an assault chopper.

“If the Army could have said, ‘OK, John, here’s what we’re gonna do. We’re gonna give you a warrant officer commission. You are going to become a pilot. We are going to send you to ’Nam, but you start out in the gun platoon,’ I would have done it,” Masaki said.

But his civilian life changed with a phone call from a man named Edward “Bud” Milton, from Visalia, Calif. Milton grew up knowing a lot of Nisei and Sansei. He wanted a Japanese American to sell insurance and memberships for the Automobile Club for the Gardena office, and he heard about Masaki.

Masaki jokes that at the time he couldn’t even spell “insurance” — but he learned about it — and sales — and worked for AAA for about three years. It put him on the path of sales, eventually also working for companies such as Dun & Bradstreet, Moore Business Forms and the New York Life Insurance Co., where he continues to this day in a retired active” status, while also doing work for some other companies.

Masaki would also get married and become a father to three children. Although the experiences could never be left completely behind, Vietnam was receding into the background of his civilian life.

But there were two big events that would have a big impact on Masaki’s life: an acrimonious divorce from his ex-wife of more than 20 years and, in 2004, becoming registered with the VA, formerly known as the Veterans Administration but now known as Veterans Affairs.

As a Vietnam vet who served in combat, he was more than eligible for its services, which in retrospect Masaki realizes he needed — and wishes he had taken advantage of earlier.

For many reasons — denial, pride or ego, not wanting to appear weak or thinking that there is a stigma to receiving treatment that could prevent them from becoming employed in certain careers — there are military vets who don’t take advantage of what the VA offers. Masaki finally saw the light and has no regrets.

For example, serving on a noisy helicopter and firing a machine gun ruined Masaki’s hearing. A base doctor in Vietnam gave him earplugs and told him to wear them, but Masaki, who also had to monitor radio transmissions, refused.

Wearing them might save his hearing, but missing a radio message could cause him to lose his life. Thanks to the VA, though, he has hearing aids that have made a huge difference in this life.

He also has COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), which he blames on having been a smoker for more than 50 years. While he doesn’t blame the Army for making him start smoking, it certainly didn’t discourage smoking, which was part of the macho culture of the time.

◊◊◊

John Masaki with his motorcycle at Los Angeles Air Force Base on Oct. 21. (Pacific Citizen photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Fifty years after serving in Vietnam, life for John Masaki is good. While he no longer can play tennis, he does play golf when he can. He gets together with friends, has spoken with young people about his Vietnam War experiences, rides his Harley and does line and ballroom dancing.

As for serving in Vietnam as a door gunner on a combat helicopter, he has no regrets. In recent years, he said he actually has thought about his wartime experiences more than when he was younger.

Masaki also realizes that his wartime experiences probably had an ill effect on some of his interpersonal relationships. All in all, in retrospect, he said, “The military did me justice.” In fact, Masaki thinks many there are many young people would benefit from having to serve their country for a couple of years.

“I know some guys probably feel ashamed that they did what they did in the service or they don’t want to discuss it at all. That’s not me,” said Masaki. “I’m proud of the fact that I served because I was told to serve. I didn’t join. But I didn’t run away from my obligations, either.