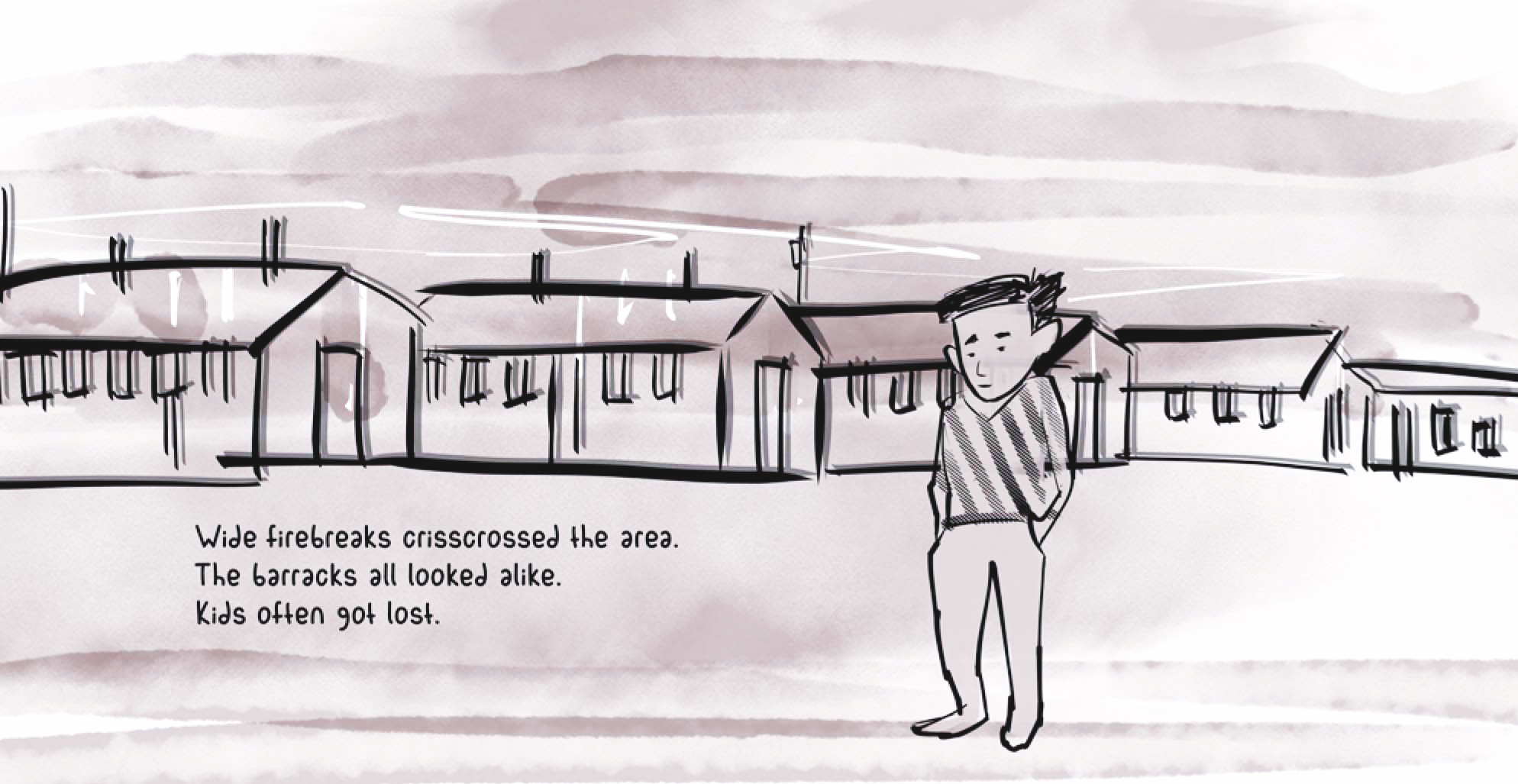

Illustrated by Matt Sasaki, this panel shows one of the “We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Wartime Incarceration‘s” three protagonists, Hiroshi Kashiwagi.

A new graphic novel makes an offer that can’t be refused.

By P.C. Staff

In recent years, different aspects of the Japanese American experience during World War II have been told via the medium of the graphic novel.

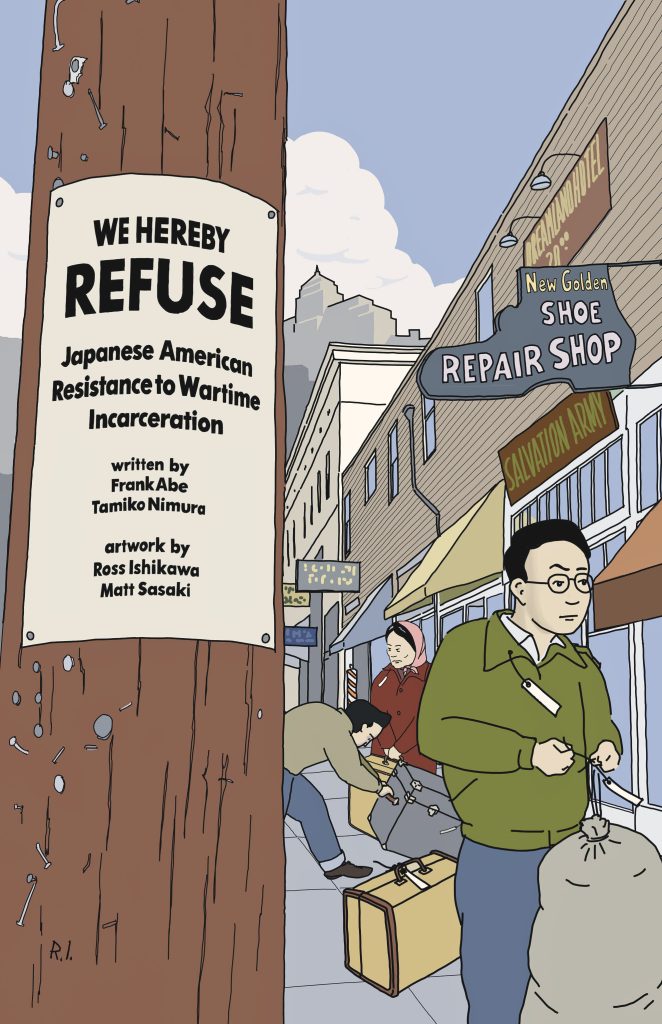

Cover of “We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Wartime Incarceration”

The year 2012 gave us “Journey of Heroes: The Story of the 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team,” written by Stacey Hayashi and illustrated by Damon Wong.

The 442nd story also got the graphic novel treatment with 2019’s “442,” courtesy of writers Koji Steven Sakai and Phinneas Kiyomura and illustrator Rob Sato (See Nov. 8, 2019 Pacific Citizen).

The late Sen. Daniel Inouye, who served in the 100th Battalion and lost an arm from combat before his career in politics, also had his story told in comic book fashion in the first issue of the second volume of the Association of the United States Army’s Medal of Honor graphic novel series (See June 26 16, 2020 Pacific Citizen).

The biggest splash, however, came in 2019 with the graphic memoir of actor George Takei’s “They Called Us Enemy,” which made the New York Times bestseller list and relayed the Japanese American incarceration experience of WWII as seen through the eyes of a young boy.

Tamiko Nimura (Photo: Josh Parmenter)

Now, in 2021, is the latest entry in the Japanese American graphic novel arena: “We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Wartime Incarceration” (ISBN 13: 978-1-63405-976-3, Chin Music Press, SRP $19.95, 160 pages).

Written by Frank Abe and Tamiko Nimura and illustrated by Ross Ishikawa and Matt Sasaki, it was released on May 18.

The book is a project of Seattle’s Wing Luke Museum, which hired the four to tell three stories of individual resistance by Japanese Americans that resulted from President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, which was signed on Feb. 19, 1942.

The protagonists are based on real people: Hajime “Jim” Akutsu, Hiroshi Kashiwagi and Mitsuye Endo, the latter being one of four Japanese Americans whose legal challenges to the effects of E.O. 9066 reached the Supreme Court, with only hers resulting in a victory.

Frank Abe (Photo: Eugene Tagawa)

For co-writer Abe, “We Hereby Refuse” is his latest deep dive into his longtime interest in examining the Japanese American resistance narrative. In 2000, he produced the documentary “Conscience and the Constitution,” which was about the draft resisters of Heart Mountain, where the Cleveland-born Abe’s father was incarcerated.

Abe also had researched the life of Akutsu, whose story of resistance (including prison time) is now seen as the inspiration for John Okada’s seminal novel “No-No Boy.” His interest in that book led to Abe co-editing “John Okada: The Life & Rediscovered Work of the Author of ‘No-No Boy’” (See Feb. 22, 2019 Pacific Citizen, tinyurl.com/yp5955k6).

According to Abe, “We Hereby Refuse” was a four-year process from getting the greenlight to getting the first run of the book published. And, even though he read comic books as a kid, writing in the medium was a different thing.

“It took me about a year to understand the graphic novel space,” Abe said. Something that helped him was Scott McCloud’s book “Understanding Comics,” which he said explained the medium as “juxtaposed pictorial images in a deliberate sequence, where often the emotion occurs in the white space between panels.”

Inspiration also came from Art Spiegelman’s acclaimed “Maus” graphic novel. Abe allowed that having experience in another visual medium, filmmaking, also helped with the learning curve of how to write for a graphic novel.

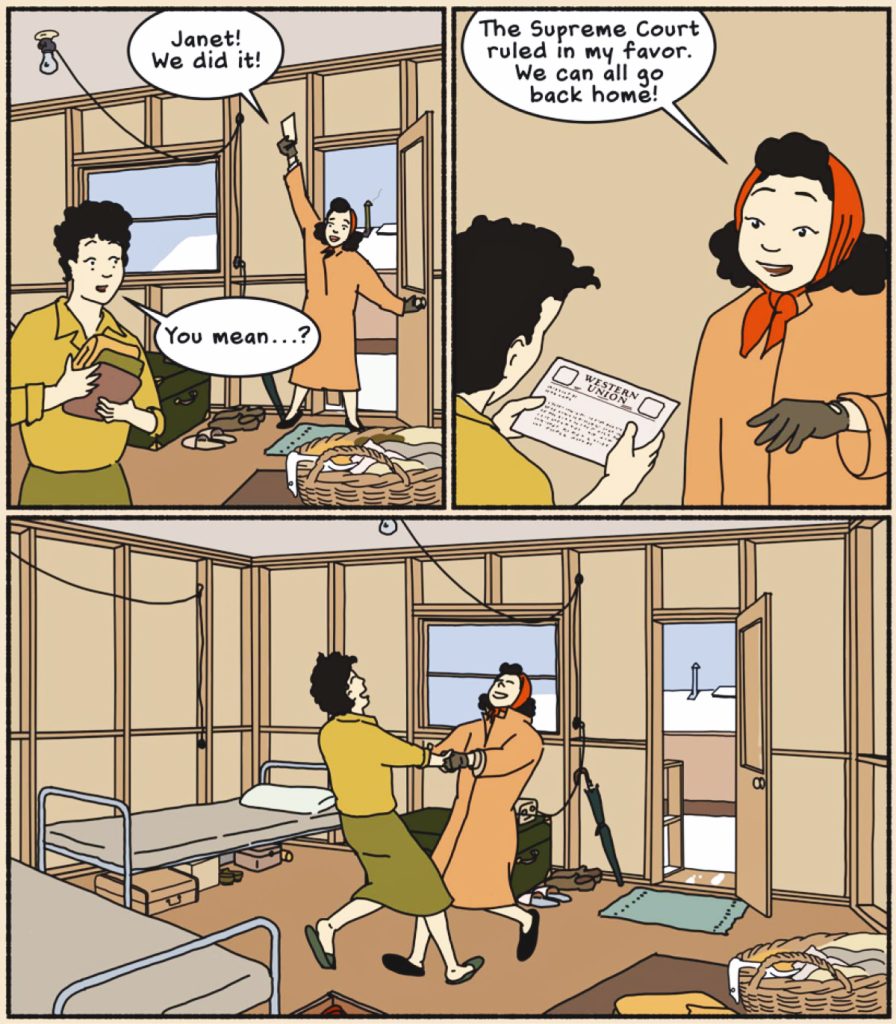

This sequence, illustrated by Ross Ishikawa, features Mitsuye Endo upon learning that she won her Supreme Court case.

In addition to the real-life “protagonists” of Akutsu, Kashiwagi and Endo, “We Hereby Refuse” also depicts — using their own words, in context, Abe pointed out — real-life wartime JACL leaders James Sakamoto (Emergency Defense Council, Seattle JACL), Saburo Kido (National JACL president), Tokutaro “Tokie” Slocum (Anti-Axis Committee, Los Angeles JACL) and Mike Masaoka (National JACL field executive), with the larger-than-life and still-controversial Masakoa among the four getting the most ink.

Abe pointed out that as writers, he and Nimura were supersticklers about making sure that what was said by the depicted JACLers was sourced and accurate. In other words, those are their words.

And, with those individuals long deceased and unable to defend themselves, Abe said it was incumbent upon him to be “studiously fair to their stories.” Going further, because they were gone, he felt it was important to not “take unwarranted dramatic license with that story.”

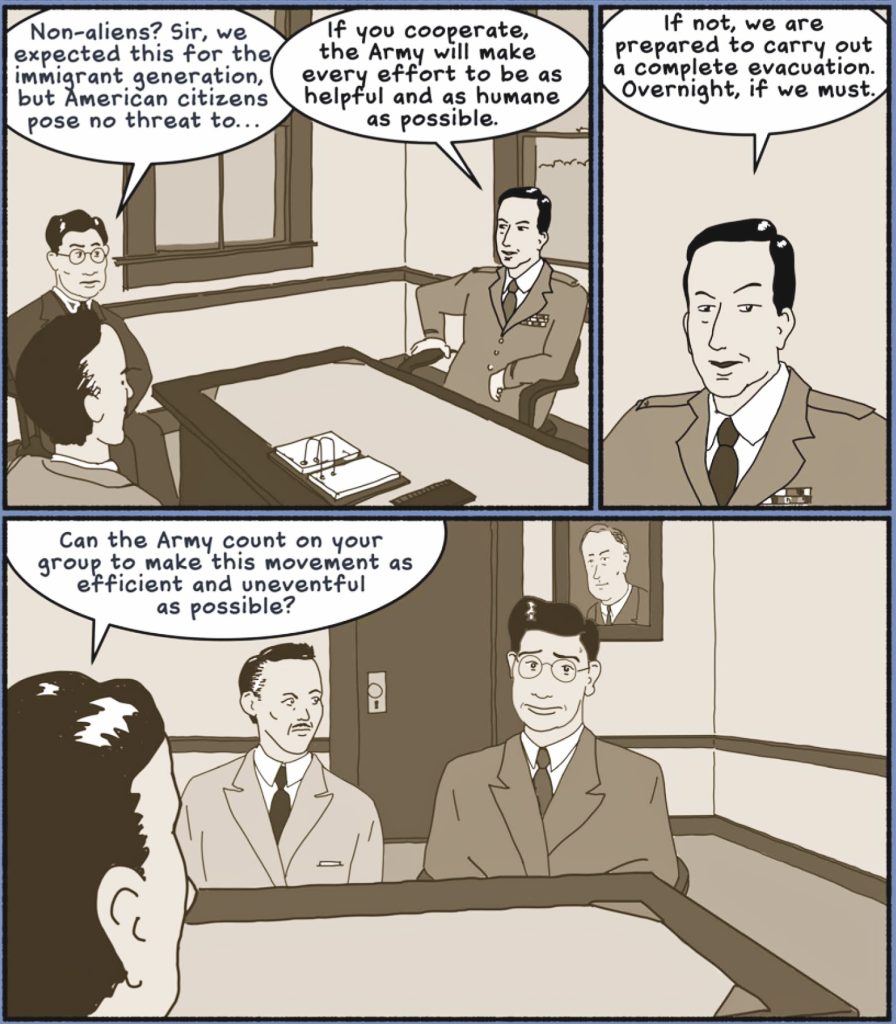

This page from “We Hereby Refuse,” illustrated by Ross Ishikawa, depicts a meeting between the JACL’s Mike Masaoka and the Army’s Karl Bendetsen.

“I took extra care to portray these men fairly within the context of the times, while using their own words,” Abe said. Furthermore, Abe wanted to emphasize that above all, it was the government that was the true malefactor that forced Japanese Americans to make decisions that under normal circumstances no one would ever have to make — and suffer the consequences of those decisions.

Artists Matt Sasaki, top, and Ross Ishikawa (Photos: Matt Sasaki and Brad Kevelin)

“The book shows through its actions, the government divided the Japanese community through a succession of orders, edicts and congressional legislation. It’s the government that drives the action in this book,” Abe said, who added that, “Our ‘characters’ are forced to navigate this new terrain for only one reason, and that is their race. Their race is the only thing they have in common.”

For Abe, one of the book’s accomplishments was telling Endo’s story. The lives and stories of Akutsu and Kashiwagi are, comparatively, better known, despite Endo having been involved in a Supreme Court case.

Because Endo neither spoke to the press nor discussed the case publicly, most people only know that she won her case and that’s all, unlike with Fred Korematsu, Gordon Hirabayashi and Minoru Yasui, whose high court losses were famously revived and revisited in the 1980s.

But including Endo’s story, and that of the Mother’s Society, which he first learned of in Mira Shimabukuro’s book “Relocating Authority,” was important because it showed how Issei and Nisei women — not just men — also took a stand against the government’s oppressive actions.

One revelation depicted in the book is that the government actually offered Endo a chance to leave camp and join her sister in Illinois if she would drop her legal case — but she refused, knowing that her stance was the more difficult choice, even though that meant staying incarcerated at the Topaz WRA Center for two more years.

“I would call it the choice that defined her character,” Abe said. “What defines Endo’s character is that when presented the choice of her personal freedom or doing what’s best for all, she chose all, she chose the community.”

Although the book is still new, the first printing of “We Hereby Refuse” sold out and a second run had to be ordered. “The book is flying off the shelves,” Abe said. “I’m pleased that the book has found its audience.”

This sequence, illustrated by Ross Ishikawa, depicts the parents of one of the protagonists, Jim Akutsu, as father Kiyonosuke Akutsu leaves his family behind to be incarcerated by the government as his wife, Nao Akutsu, watches helplessly.