Asakawa has been traveling the country on a book tour, happy to talk about his love of all things Japanese, especially food. (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

Author Gil Asakawa traces the paths Japanese food took to be loved in America.

By George Toshio Johnston, Senior Editor

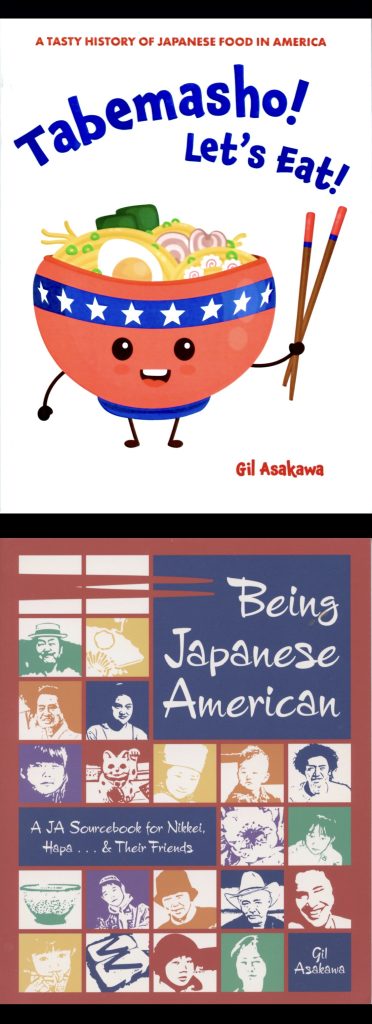

Author Gil Asakawa’s books are a celebration of Japanese American history and heritage.

Of the three books Denver-based journalist Gil Asakawa has written — 1991’s “The Toy Book” (with his pal, Leland Rucker) and 2015’s “Being Japanese American: A Sourcebook for Nikkei, Hapa … and Their Friends” — it’s likely safe to say that his new one is closest to his heart.

Enjoying that last bit of a fine Japanese meal. (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

That’s because the foodophile’s stomach is heart-adjacent.

“Tabemasho! Let’s Eat!: A Tasty History of Japanese Food in America” (p-ISBN 978-1-61172-068-6; SRP $18.95), published in August by Stone Bridge Press, is Asakawa’s informative and chatty exploration-cum memoir of the sundry Japanese foods he grew up with, mixed with his memories of first encounters with those victuals and his historical research on how many of those foods originated, with some actually reaching these shores to become as American as pizza pie.

“I really had a lot of fun writing it,” Asakawa told the Pacific Citizen, for which he has in the past served on its Editorial Board, including more than one stint as P.C. board chair.

“I think it’s fascinating and important to cover, not just kind of the tradition in the history of Japanese food in Japan, but how it adapted to suit the tastes of Americans and follow how it became popular and why it became popular,” Asakawa continued. For instance, he gives credit to the restaurant chain Benihana, which, as he puts it, “is what made Japanese food safe for Middle America.”

Although it might simply appear to be a case of “write what you know,” since Asakawa is one of those gourmands who regularly posts photos of his latest feasts of all kinds of cuisines on his social media feeds, turning his particular passion for Japanese — and Japanese American — foods into a book was, ahem, “natto” as easy it might seem, despite having a Hokkaido-born Japanese mother and Hawaii-born Japanese American father.

“I did a lot of research, and I learned a lot of stuff to write ‘Tabemasho!’” Asakawa said. “I was surprised at how much I didn’t know about the food that I love.” In other words, even if you’ve grown up around it, there is still something about Asakawa’s deep dive into learning about Japanese food that you probably did not know.

Part of Asakawa’s journey into Nihonshoku includes “foreign” foods like ramen and curry — arguably even tonkatsu —that have become part of the modern menu of foods Japanese people eat nowadays.

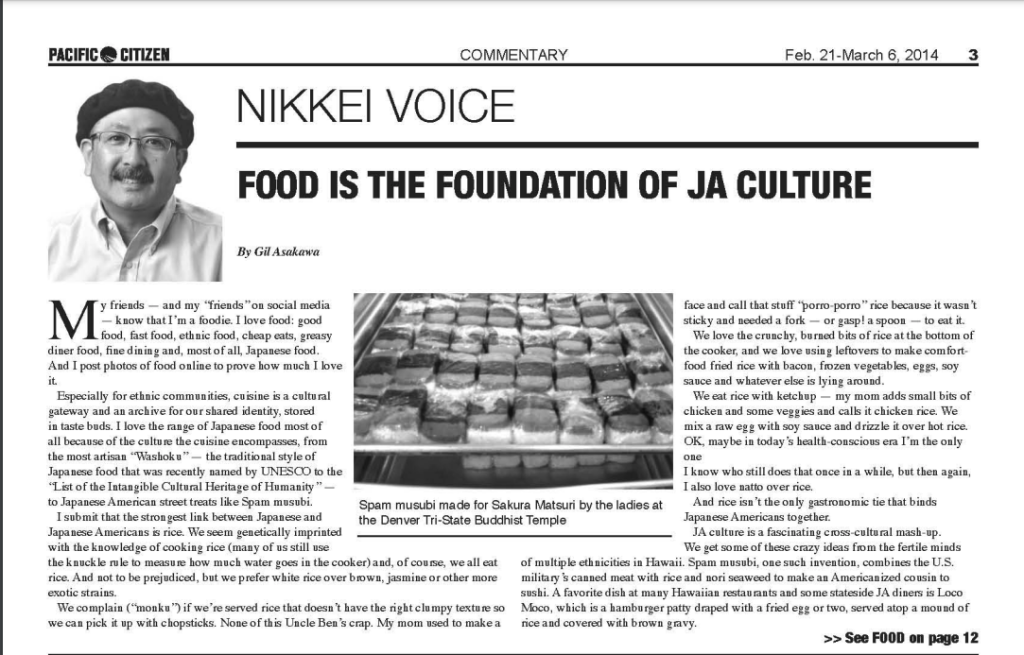

Writing and blogging about Japanese and Japanese American cuisine is nothing new for Asakawa, as evidenced by this Pacific Citizen column from 2014.

“One of the things that I’ve learned about Japanese food in general is that a lot of the things that we think of as Japanese food didn’t originate in Japan and are not necessarily traditional in the historical sense,” Asakawa pointed out. For example, curry is so popular in Japan that many people there eat it at least once a week. But Japanese curry is not like curry from India. The Japanee “took it from the British and then adapted it for the Japanese palette.”

Speaking of menus, one of the items Asakawa used in his research for “Tabemasho!” was a 1952 menu from Los Angeles restaurant Imperial Gardens that provides a snapshot of what Japanese food used to mean to people in America. The restaurant’s menu “only featured three kinds of food,” said Asakawa. “Sukiyaki, teriyaki and tempura. Those three were the mains.”

But, in fairness, it was still the early 1950s, not too far removed from the end of World War II, when what most non-Japanese Americans knew of Japanese food was what American GIs coming back from the occupation of Japan remembered eating.

Ironically, Asakawa noted that in Denver, “It’s hard to find a Japanese restaurant that will serve sukiyaki anymore — but that used to be the standard.” In “Tabemasho!” Asakawa, once a former music critic for Denver’s alt-weekly Westword, relays that the erstwhile popularity of sukiyaki the dish is why the 1963 No. 1 pop hit in America, “Sukiyaki,” aka “Ue o Muite Arukō,” got its name.

In “Tabemasho!” Asakawa also gives ink to hugely popular Japanese American dishes — spam musubi, the California roll (with avocado as an ingredient) and mochi ice cream, for example — that might be difficult to find on any menu in Japan. Yet, those are examples of what were in actuality fusion cuisine (before that became a label) borne of the necessity of using local ingredients, whatever was available or plain old Yankee ingenuity.

Part of Asakawa’s fascination with Japanese food also comes from being old enough to remember when Japanese food was a punchline.

Seaweed?! Yuck! Sushi? With raw fish?! Eeew!

Gil Asakawa captures a photo of his meal before digging in. (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

Today, when supermarkets selling prepackaged sushi are ubiquitous, some young people might find that hard to believe. But Asakawa remembers how in the 1985 movie “The Breakfast Club,” the character played by Molly Ringwald was mocked by Judd Nelson’s character for bringing sushi for lunch. (That just might be par for the course, however, since the movie’s writer-director was John Hughes, who was also repugnantly responsible for Long Duk Dong in 1984’s “Sixteen Candles.”)

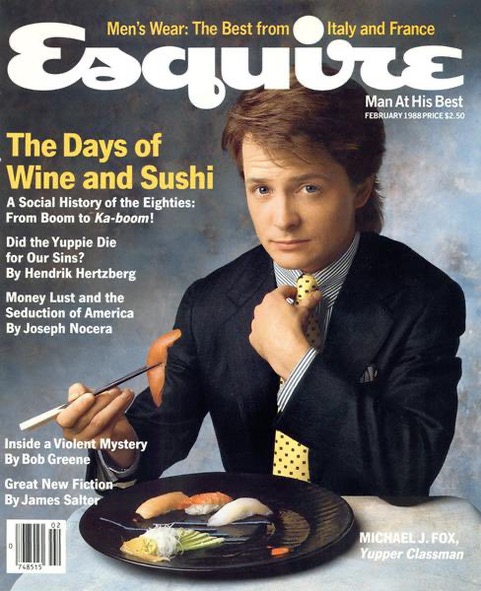

Michael J. Fox was featured on the cover of Esquire magazine in the late 1980s with a plate of sushi, sparking conversation about its growing popularity in America.

Fast-forward to the end of the 1980s, though, and Asakawa notes that “Michael J. Fox was on the cover of Esquire magazine eating a plate of sushi.” The image of Japanese food — for the majority of white Americans, at least — was changing.

But Fox and Esquire can only claim partial credit for the changing perception of Japanese food in America. Another factor: instant ramen. Originally developed in the 1950s by Momofuku Ando, an immigrant from Taiwan, instant ramen, followed in the 1970s by Cup Noodle, were hits in Japan.

“Because it was so damn cheap,” both versions, especially the square noodle brick version, would also find footing in the U.S. with hungry and impoverished college students — no doubt still true — “even though it wasn’t the world’s greatest ramen.” It may have, however, been the unintentional gateway to seeking out better ramen. For the past few years on these shores, ramen restaurants, many of which are U.S. outposts of Japan-based chains, have been getting rated and reviewed by “ramen connoisseurs” on social media sites.

Combined with the continued soft power appeal of Hello Kitty, manga and anime, the popularity of Japanese baseball players like Shohei Ohtani and progression of acceptance through the decades of Japanese foods from sukiyaki to sushi to ramen, Asakawa’s timing for “Tabemasho!” is a recipe for success.

Gil Asakawa enjoys a meal with the P.C. staff. (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

As for what Japanese food item might be next to find American fans, Asakawa knows it would be foolhardy to hazard a guess, though he thinks yakisoba might have a chance to cross over.

For Asakawa, it’s far easier to predict the foods that will probably never stand a chance of crossing over, for a variety of reasons. Horse and whale, for instance. Natto — mucilaginous and funky fermented soybeans — remains another unlikely candidate. For Calpis, as it’s known in Japan, to stand a chance in the U.S. market, the beverage had to be rebranded as Calpico. One of his personal favorites is karintō, which he says has a striking resemblance to what you’d find in your cat’s litterbox. (Despite that imagery, karintō’s coloring and sweetness come from a brown sugar coating, which gives it its dark color. Appearances can be deceiving, after all.)

Asakawa just hopes that anyone who reads “Tabemasho!” finishes with a couple of outcomes.

“I hope it makes them hungry,” he said. “And I hope it makes them want to try different kinds of Japanese food.”

The Asakawa family at Benihana restaurant in Virginia, where they enjoyed a meal with a family friend. Asakawa, in his own words, is the “chubby third one from the right, ready to pounce with my hashi.” (Photo: Gil Asakawa)