”Picture Bride,” from 1994, stars Yuki Kudo and Tamlyn Tomita and was directed by the late Kayo Hatta.

By Rob Buscher, Contributor

Following the success of Tadaima! Virtual Pilgrimage that took place over nine weeks during summer 2020, Tadaima returns for a shorter four-week iteration from Aug. 29-Sept. 25 and will feature online exhibits, workshops, performances, lectures, panel discussions, film screenings, a community archive and more.

This completely free program is a collaborative undertaking by more than 60 Japanese American community organizations and seeks to continue building the connections that were developed throughout last year’s virtual programming.

As curator of the Tadaima online film festival, I set out to program Tadaima 2021 to address many of the themes that I observed to be central in the nationwide discourse among Japanese Americans over this past year of the pandemic.

As curator of the Tadaima online film festival, I set out to program Tadaima 2021 to address many of the themes that I observed to be central in the nationwide discourse among Japanese Americans over this past year of the pandemic.

Among these are: Representations of Japanese-ness in Hollywood, Remembrance and Interpretation, Reconciliation, Social Justice and Inter-ethnic Solidarity and Japanese Identity. Rather than dividing films of a particular theme into separate weeks as we did last year, nearly the entire film program will be available throughout the duration of the virtual pilgrimage unless noted.

The first Tadaima program focused largely on the history and remembrance of wartime incarceration, which is, of course, present this year as well. However, many of the films included in this year’s festival are not explicitly related to the wartime incarceration. Those that are tend to offer contemporary interpretations through the lens of Sansei, Yonsei and beyond.

Fewer camp survivors remain with each passing year, and it will soon be up to those of us who did not experience the wartime incarceration directly to pick up the mantle by continuing to share these stories with future generations in new and interesting ways.

“Gabriel’s Heart Mountain 3.0”

One example can be found in the short film “Gabriel’s Heart Mountain 3.0,” co-directed by Renee Tajima-Peña and her son, Gabriel, in which he leads a group of middle-schoolers to develop a Minecraft rendition of Manzanar.

A wholly different approach at interpretation is offered by filmmaker Rea Tajiri, whose experimental documentary “History and Memory: For Akiko and Takashige” is itself an exercise in piecing together the past through incomplete family narratives.

In a more literal sense, films like “Picture Bride” (available Sept. 6-12 only) present stories related to the Hawaiian plantation era of early Japanese immigration, lovingly told by the descendants of Japanese Hawaiian plantation workers. This year also includes lesser-known stories like “Hatsu,” a short film about the Japanese Peruvian experience during World War II.

“Hatsu”

A large section of the program has been dedicated to parallel experiences of oppression that Japanese Americans share with other historically marginalized communities.

Jon Osaki’s short documentary “Reparations” makes a compelling case for why our community needs to take an active role in advocating for African American reparations. Akira Boch’s film “9066 to 9/11” connects the Japanese American experience in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor to that which Muslim Americans faced after the Sept. 11 terrorist attack.

Rex Moribe’s “Dear Thalia” and Ciara Lacy’s “Out of State” (available Sept. 19-25 only) reveal the relative privilege that Japanese Hawaiians possess, comparative to the marginalization of Native Hawaiians who experience homelessness and, in some cases, enter the carceral system in greater numbers than any ethnic group in Hawaii.

Of particular note is the new release documentary “Manzanar, Diverted: When Water Becomes Dust” (available Sept. 23-25 only), a compelling reminder that all land we inhabit in the United States once belonged to indigenous communities, as well as the need for all people to work together toward environmental justice.

Another theme that emerged in the wake of the Atlanta Spa Shootings is the role that mainstream media stereotypes have on Asian Americans. Related to this is a section of the program of which I am particularly proud — the retrospective of Postwar Hollywood films.

“Japanese War Bride”

In last year’s program, we explored how Hollywood colluded with the U.S. military to produce anti-Japanese propaganda films. American filmmakers continued working under the guidance of the U.S. military in the postwar era, only this time, it was to create “friendship propaganda” between the U.S. and Japan, our new Cold War ally.

“Japanese War Bride,” starring Shirley Yamaguchi (better known to Japanese audiences as Ri Koran and renowned for her roles in Sino-Japanese Imperial propaganda films), offers the first attempt at destigmatizing interracial relationships between Japanese women and white American men.

Similar themes can be seen in 1957’s “Sayonara” (available Sept. 6-12 only), starring Marlon Brando and Miyoshi Umeki (“Flower Drum Song”), who until recently was the only Asian female to win an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress.

“Bridge to the Sun”

In contrast to the begrudging acceptance of these white male/Asian female filmic relationships, Nisei James Shigeta stars in “Bridge to the Sun” (available Sept. 6-12 only) as the Japanese diplomat husband of a white American woman whose relationship is doomed by the war. Shigeta would go on to become something of an Asian male sex symbol for a brief period during the late 1950s and early ’60s, culminating in his starring role in “Flower Drum Song.”

Although shown in a more sympathetic light than silent film actor Sessue Hayakawa, an Issei who became Hollywood’s first male sex symbol in the mid-1910s, Shigeta also embodied many of the same qualities in his early romantic roles for the postwar generation.

“The Dragon Painter”

On that note, another highlight of the festival is Hayakawa’s “The Dragon Painter,” a silent film produced in 1919 in which he stars opposite his wife, Tsuru Aoki, an Issei actress who also made it big in early Hollywood.

In advance of the 100th anniversary of the film’s release, the Philadelphia Asian American Film Festival commissioned indie rock musician Goh Nakamura to compose a new original soundtrack to the film in 2017, which accompanies the version of the film being shown.

Nakamura will also be making an onscreen appearance as we screen the “Surrogate Valentine” trilogy of indie films in which he stars as a fictionalized version of himself. Join me on Sept. 16 at 5 p.m. PT for a livestream conversation with Goh, where we will delve into his career as an actor and musician.

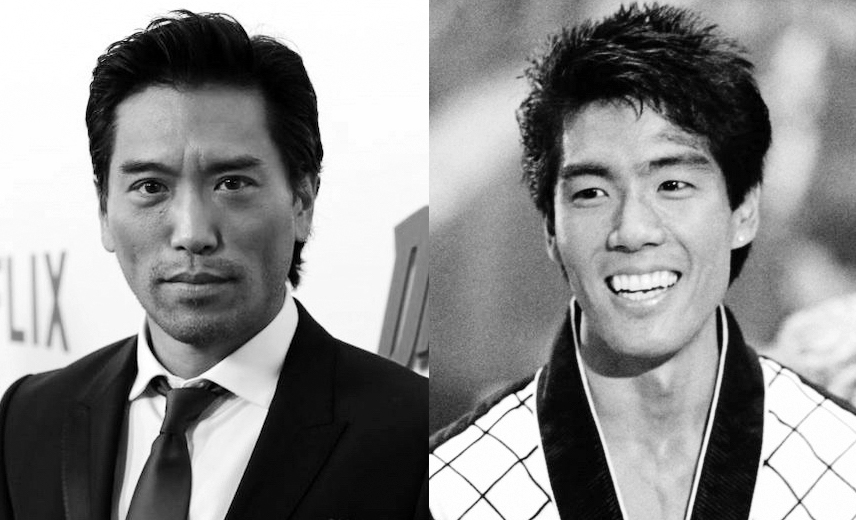

Another livestream session that I am excited about is one that I have affectionately titled, “Say Hello to the Bad Guys,” which features Japanese American actor Yuji Okumoto (“The Karate Kid II”) and Japanese Canadian actor Peter Shinkoda (“Daredevil”).

Actors Peter Shinkoda and Yuji Okumoto

On Sept. 3 at 7 p.m. PT, I will be moderating a panel with Okumoto and Shinkoda related to Japanese masculinity and negative stereotyping within Hollywood that has often relegated Japanese men to the role of villain.

With 2021 marking the 80th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, reconciliation is another central theme that we explore through cinema on both sides of the Pacific. “Forgive, Don’t Forget” follows the journey of an American filmmaker as he attempts to reunite a surrendered Japanese sword to its original Japanese owner.

“Samurai in the Oregon Sky” tells a parallel story of redemption where Japanese pilot Nobuo Fujita, who flew the only bombing mission over the U.S. mainland during WWII, is invited back to the region, where he would begin a 35-year friendship with the people of a small Oregon town he once sought to destroy.

Another film in this section, “When the Fog Clears,” recounts the stories of Japanese and American families who were bereaved through the Battle of Attu and how they connected nearly 70 years later through their mutual sense of loss and forgiveness.

One of the more unique stories in this section is told by the short documentary “A House in the Garden: Shofuso and Modernism,” which explores the artistic interconnections between renowned Nisei woodworker and architect George Nakashima, the husband-and-wife design team of Antonin Raymond and Noémi Pernessin Raymond and Japanese architect Junzo Yoshimura — who designed and built a traditional Japanese house at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art just eight years after WWII ended.

The final section explores topics related to Japanese culture and identity, particularly the shifting definitions of Japanese-ness as both Japan and the Japanese diaspora become more diverse.

Greg Lam’s documentary “Being Japanese” explores the growing diversity in Japan while asking the fundamental question: What makes a Japanese person Japanese?

“Hafu”

Shot almost a decade ago, “Hafu: The Mixed-Race Experience in Japan” (available Aug. 29- Sept. 14 only) approaches a similar topic from the specific lens of five biracial Japanese individuals, long before Naomi Osaka or Rui Hachimura became household names.

Two episodes of the PBS TV food documentary series “Family Ingredients” will also be showcased, which highlight the influence that chefs of Japanese and Okinawan ancestry have on contemporary Hawaiian cuisine.

One of the programs I am most excited about is the selection of music videos by hip-hop artist and spoken-word poet G Yamazawa that will be featured in this festival. Born and raised in Durham, N.C., the curated collection of Yamazawa’s music videos imaginatively explore his myriad identity as a Shin-Nisei Japanese American from the American South.

G Yamazawa

Join us for a livestream conversation on Sept. 2 at 5 p.m. PT, where we will discuss the intricacies of multiple overlapping identity as conveyed through film and music.

I hope this program will contribute in some small way at least toward continuing to foster these community conversations as we endure what I hope is the last phase of the pandemic. While the pandemic has forced us to physically distance ourselves, as a mixed-race Yonsei who was raised on the East Coast, I have never felt closer to the Japanese American community than I have over the past year, in large part through the many connections I developed through Tadaima.

I believe that we will emerge stronger after the pandemic than we were before, having had this time to reflect, connect and realign our mission as the stewards of Japanese American legacy organizations and the community-at-large. Thank you for joining us for Tadaima 2021, and whether you are a returning audience member or first-time attendee, Okaeri (“Welcome Home”).

For more details on the Tadaima! Virtual Pilgrimage and to watch these films and others free online from Aug. 29-Sept. 25, visit www.jampilgrimages.com/films-tadaima-2021.