A Harada family portrait, 1928. Pictured back row from left are Mine, Mary, Calvin, Masa Atsu, Sumi and Clark; front row from left are Yoshizo, Ken, Harold and Jukichi Harada. (Photo: Courtesy of the museum of Riverside, Riverside, Calif., courtesy of the Harada Family Archival Collection)

The Riverside, Calif., landmark is awarded a grant from the National Park Service, but more action is needed to preserve this historic site.

[Editor’s note: Since the publication of this article, the National Trust for Historic Preservation in late September included Harada House among its annual list of 11 Most Endangered Historic Places in America. To view the complete list, visit tinyurl.com/y3woojv3. To view the Los Angeles Times’ article on the inclusion of Harada House to the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s annual list, visit tinyurl.com/yy8yjh4m]By Naomi Harada, Judy Lee, Robyn Peterson, NPS and P.C. Staff

‘I won’t sell. You can murder me. You can throw me into the sea. I won’t sell.’

— Jukichi Harada’s response after being offered more than what he had paid for the long-desired home in Riverside, Calif. (1915)

After losing their beloved 5-year-old son to diphtheria, Jukichi Harada and his wife, Ken, sought a home in a safe, clean and healthy neighborhood. The year was 1915.

Neighbors objected and offered to buy the house, built in 1884 and located at 3356 Lemon St., in Riverside, Calif., fueled by the atmosphere of “Yellow Peril.” When they were rebuked, the neighbors sought the aid of the state attorney general to prosecute the Harada’s for violating the Alien Land Law, which prohibited Asian immigrants from buying property in California.

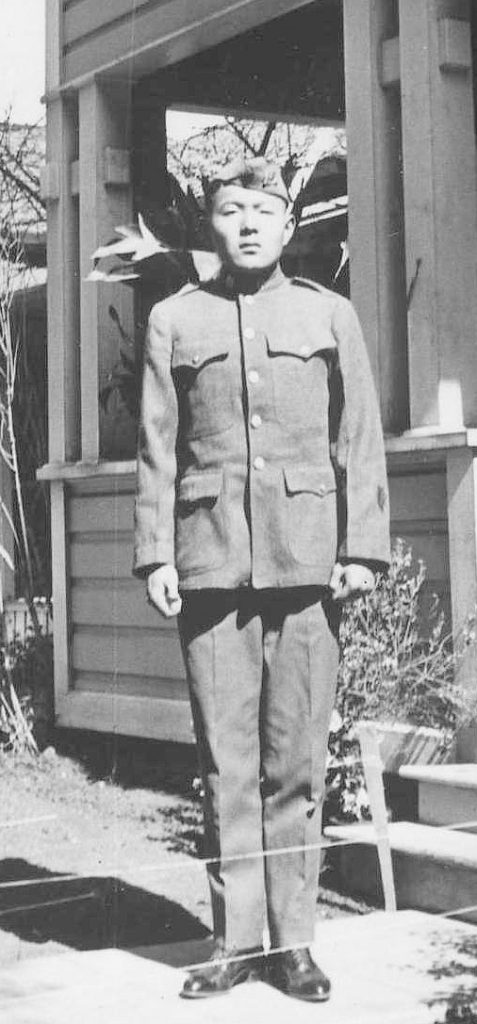

Yoshizo Harada at the Harada House, circa 1930 (Photo: Courtesy of the Museum of Riverside, Riverside, Calif., the Harada Family Archival Collection)

The Harada’s had placed the title of the home in the names of their three youngest children, Mine, Sumi and Yoshizo, who were U.S. citizens. When the couple won the landmark Superior Court case California v. Harada in 1918, it was a significant decision.

Presiding Judge Hugh Craig stated, “They are American citizens of somewhat humble station, it may be, but still entitled to equal protection of our land. … The political rights of American citizens are the same, no matter what their parentage.”

Some 25 years later, the Harada family again suffered the effects of “Yellow Peril,” and like many others were uprooted by the incarceration experience of World War II. But unlike the majority of Japanese Americans, when their incarceration finally ended, the Harada home had not been sold or taken away.

Instead, it had been cared for by Jess Stebler, a family friend. Thus, daughter Sumi Harada was able to offer temporary housing to returning Japanese Americans in Riverside. Both of her parents, Jukichi and Ken, passed away while incarcerated during WWII. For years, Sumi continued to live at the family home and served as the keeper of its history and hosted family gatherings there until her passing.

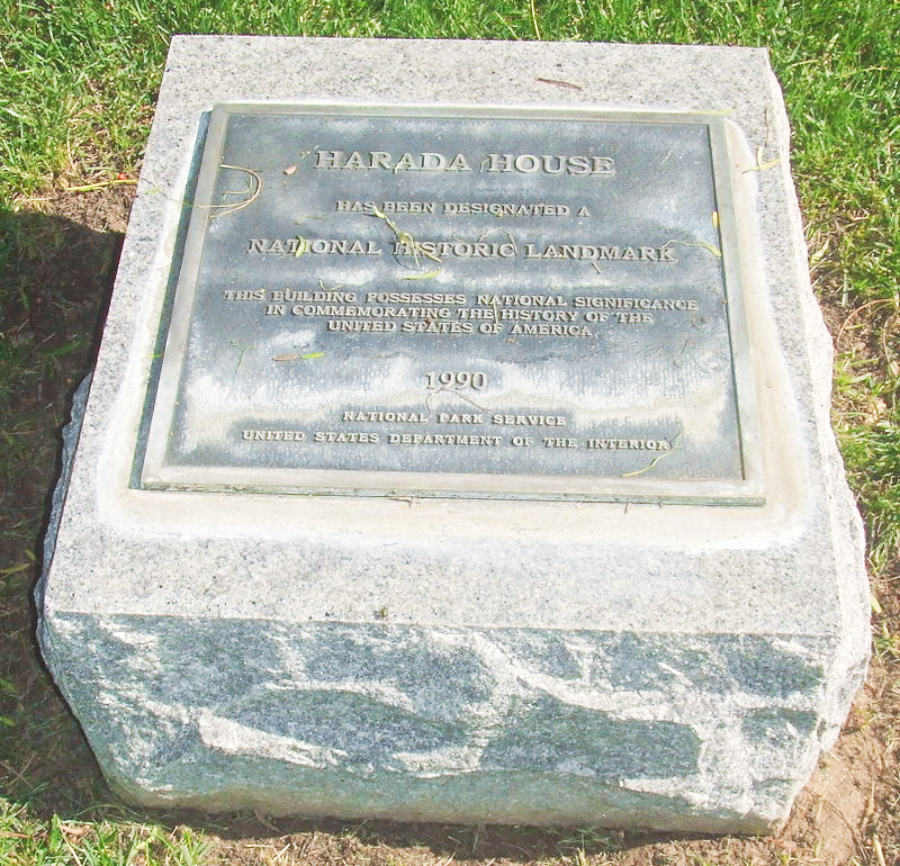

The house, along with primary artifacts and resources, was eventually donated by the Harada family to the City of Riverside under the stewardship of the Museum of Riverside. Because of the role the Harada House played in the landmark case challenging California’s Alien Land Law and the story of a local family having endured the historic Japanese American incarceration experience, the Harada House is one of two National Historic Landmarks in Riverside, having received its official designation in 1990.

As such, it is unique among Japanese American sites of significance since it documents the story of a single family placed within the context of a group of people in an American historical event. Although the Harada House’s 20th-century stories and records now endure into the 21st century, the physical structure of the 1880s home needs attention and rehabilitation.

Harada House prior to work being done in 2018. (Photo: Pacific Citizen)

In today’s turbulent times, could the fetid waters of “Yellow Peril” once again be churning, leading to more xenophobic legislation? We have seen negative responses and treatment of specific immigrant groups in the wake of 9/11.

Recent images of U.S border agents’ placement of children in cages are chilling, with some calling for new camps, citing the Japanese American incarceration experience as precedent. And now, the COVID-19 outbreak has spurred the finger-pointing blame toward an ethnic group, augmented by the American president persistently calling it the “Chinese virus.”

“Home” is now a very relevant topic. The COVID-19 outbreak has caused us to “stay at home.” Most of us are fortunate to have a home, but if the Alien Land Law were still in effect today and if the Harada case had had a different outcome, how many of us would have a home?

As of 2018, there are 44.7 million immigrants in the U.S. But the reality is, apart from Native Americans and Native Hawaiians, we are all immigrants.

“Places associated with the Asian American Pacific Islander heritage are sorely needed to provide the general public with easily accessible, readily digested, readily affordable, educational, recreational and historically responsible information about this rapidly growing ‘racial’ demographic in America,” stated Franklin Odo in his introduction to a collection of essays for the National Park Service. Odo continued, “This understanding will empower the U.S. to act positively to secure their roles going forward in complex times, when issues of race, class, gender and religion make increasing demands on the political and moral character and stamina of the entire nation.” (Odo, an author, scholar, activist and historian, was the founding director of the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, 1997-2010.)

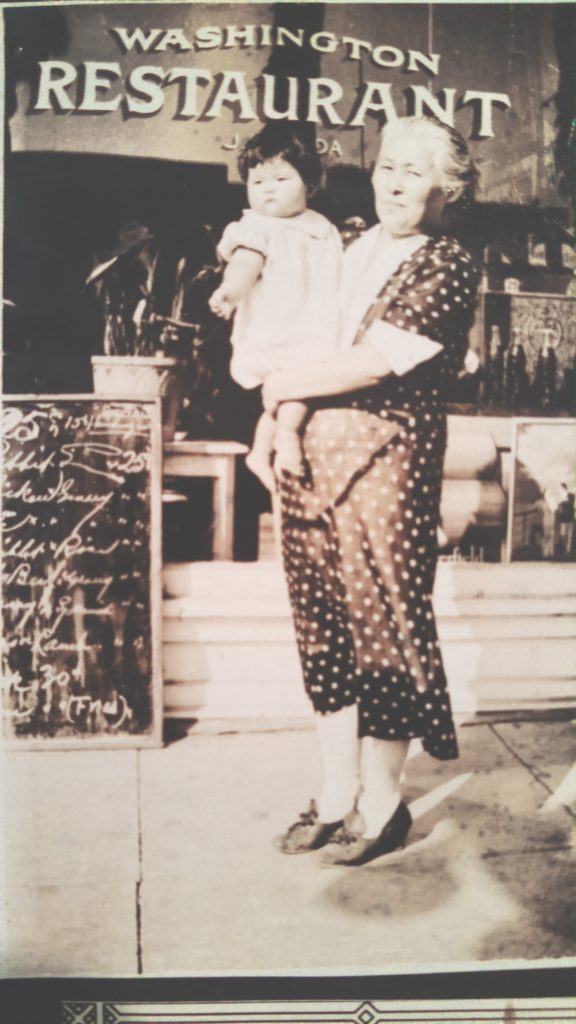

Ken Harada and her grandchild in front of the family restaurant (Photo: Courtesy of Naomi Harada)

So, why should the Harada House and its stories be preserved and protected?

Because we need to be reminded of the importance of our democracy. We need to continually be aware that our rights, “our certain inalienable rights,” can be threatened. And we must be steadfast in our guardianship of and advocacy for those rights. The Harada House and its stories help to solidify the importance of our democracy. They are stories of our community — they are our strength.

“The Harada House represents the activation of democracy,” said Naomi Harada. “Historical preservation helps to convey concepts: sitting in the house, imagining the conversations that transpired between family members, seeing and reading the inscription on my father’s boyhood bedroom in his familiar scrawl: ‘Evacuated on May 23, 1942. Sat. 7 a.m.’ have a powerful impact of how historical events can jar one into the here and now. That jarring may motivate those to think and act for a more just and fair society. That is my hope for the preservation of the Harada House.”

Action can be implemented by engaging legislators to advocate for funding the rehabilitation of the Harada House and developing the site as a civil rights and social justice interpretive center.

Action can also continue with volunteerism and services to the Museum of Riverside and the Harada House Foundation. In addition, disseminating information about the significance of the Harada House to the public at large will continue to educate current and future generations. These actions in turn strengthen our community.

Recently, the Harada House was awarded on Aug. 20 a “Saving America’s Treasures” grant in the amount of $500,000 from the National Park Service, in partnership with the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities to support the preservation of nationally significant historic properties and collections.

According to Riverside JACL’s Judy Lee, who also is a member of the Harada House Foundation, the Harada House is “the only recipient in California, as 42 grants were given nationally. It is an honor that this icon of social and legislative justice for Nikkei is recognized as a treasure by the federal government.”

In 2019, Congress appropriated funding for “Save America’s Treasures” from the Historic Preservation Fund, which uses revenue from federal oil leases to provide a broad range of preservation assistance without expending tax dollars.

Harada House NHL plaque (Photo: Pacific Citizen)

The program requires applicants to leverage project funds from other sources to match the grant money dollar for dollar. This award of $12.8 million will leverage more than $25.9 million in private and public investment.

“From conserving the papers and artifacts of William ‘Count’ Basie to stabilizing a sandstone cliff dwelling of the sandstone cliff dwelling of the Ancestral Puebloan culture, these grants enable educational institutions, museums, tribes and local governments to preserve significant historic properties and collections for ongoing purposes of inspiration and education,” said Margaret Everson, counselor to the secretary, exercising the delegated authority of the NPS director.

The Federal “Save America’s Treasures” program was established in 1998 and is carried out in partnership with IMLS, NEA and NEH. From 1999-2018, the program provided $323 million to more than 1,200 projects to preserve and conserve nationally significant collections, artifacts, structures and sites. Requiring dollar-for-dollar private match, the grants leveraged more than $479 million in private investment and supported more than 16,000 local jobs.

In order to meet the requirements for this matching grant, the Harada House Foundation will launch an immediate fundraising campaign.

“We are delighted as this is a significant step toward our overall $6.5 million fundraising goal,” said Lee in an email to the Pacific Citizen. “[We are] one of only 10 projects to be fully funded at the maximum $500,000 (matching) grant level.”

“The goals are to rehabilitate the house and to develop an interpretive center for civil rights and social justice, using the Harada House story as a framework,” said Naomi Harada.

In additional news regarding the Harada House, the California State Historic Resources Commission met on Aug. 14 to discuss various state nominations, of which the Harada House was one, having been nominated for California State Historic Landmark status.

“While we await the final announcement of that designation, we would like to note that at the meeting, many of the nominated sites represented ethnic and diverse communities in California, reflecting an important trend in historic preservation,” Lee wrote to the P.C. “This follows what the National Trust for Historic Preservation — NTHP — has been trying to encourage when it helped to sponsor the first Asian and Pacific American Historic Preservation Forum — APIAHiP, San Francisco, 2010 — a conference that meets every other year, most recently in Honolulu in January.”

In addition, the Harada House Foundation awaits anxiously the announcement this fall of the NTHP’s “11 Most Endangered Historic Places” for 2020.

For more information on the Harada House Foundation and its fundraising goal efforts, visit haradahousefoundation.org or www.riversideca.gov/museum/haradahouse/ or view its Facebook page.