An archival image of George Nakashima with his daughter, Mira (Photo: Courtesy of the George Nakashima Foundation for Peace)

A new book offers an ‘intimate window’ into the

internationally recognized woodworker’s philosophy of furniture making.

By Emily Murase, Contributor

Mira Nakashima, daughter of celebrated woodworker George Nakashima (1905-90), is criss-crossing the country to participate in book-signing events for the recently released “The Nakashima Process Book.” She explains the book as being “No longer a catalog, but an intimate window into how and why we do what we do.”

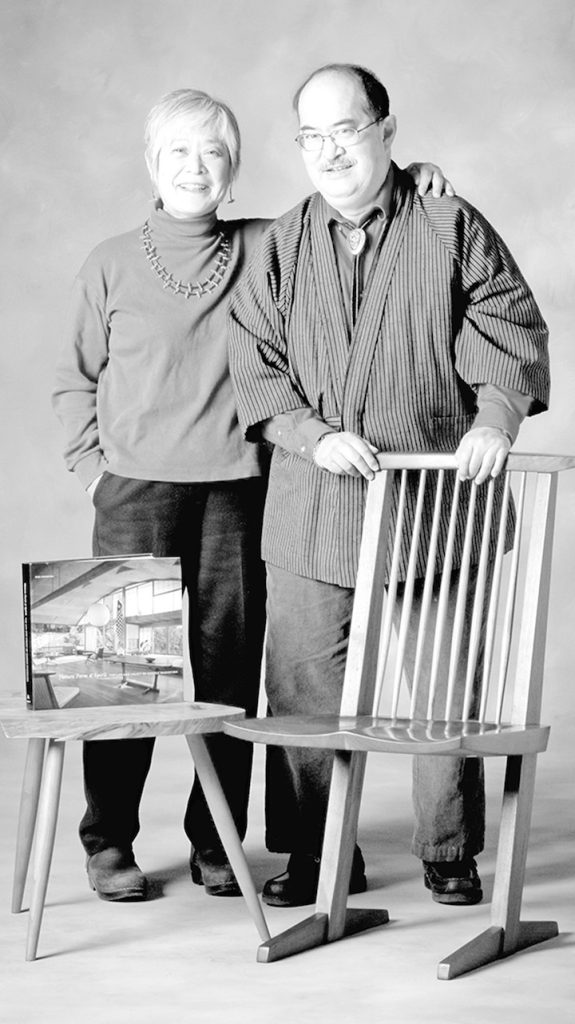

Mira with the Mira chair

George Nakashima’s internationally recognized handmade wood furniture reflects a particular philosophy: “… We can walk in step with a tree to release the joy in her grains, to join with her to realize her potentials, to enhance the environments of man.”

While known for one-of-a-kind home furnishings, Nakashima also created a landmark Sacred Peace Altar, as well as spectacular Peace Tables, large-format conference tables, in New York, Russia and India that have inspired new ways to communicate globally.

Mira Nakashima in 1947 with her parents, George and Marion

Mira Nakashima was born in Seattle, just before she and her family were incarcerated at Minidoka during World War II. At Minidoka, her Nisei father met and worked closely with master carpenter Gentaro Hikogawa. Within a year, one of her father’s previous employers, the influential architect Antonin Raymond, petitioned for the family’s release, and they were able to resettle in New Hope, Pa., located outside of Philadelphia, where Raymond maintained a working farm. Despite an architecture degree from MIT, her father rejected architecture as a profession and instead started his own woodworking studio.

Currently president and creative director of George Nakashima Woodworkers, Mira Nakashima joined her father’s studio in 1970 after graduating from Harvard University and completing a master’s degree in architecture from Waseda University in Tokyo.

She took time from her busy travel schedule to discuss with Emily Murase for the Pacific Citizen about various influences on her work and the new book.

Emily Murase: I understand you were in the first class of women that Harvard graduated. What was that experience like? How did it shape you?

Mira Nakashima: I graduated from Solebury School in New Hope, where we were encouraged to shoot for the top. My father had studied for two weeks at Harvard but didn’t care for the instruction there and transferred to MIT to complete a degree in architecture.

Mira Nakashima (Photo: Manolo Yllera)

Women were not awarded Harvard degrees for many years, though they attended classes there, and graduated from Radcliffe. Most of my classes were on the Harvard campus, and Harvard decided to award Harvard-Radcliffe diplomas in 1963, the year I graduated.

Since there were not very many Japanese Americans in the area where I grew up, I was used to looking different than everyone else, so the fact that there were not very many Asians in Cambridge didn’t really bother me.

Murase: After graduation, you spent time in Japan, eventually earning a master’s degree from Waseda University. How did your time in Japan influence your craft?

Nakashima: In college, I was involved in Dance Group and Choral Society for four years and served as president of both groups my senior year. I graduated in spring 1963 and continued my dance education at the Connecticut School of Dance for the summer.

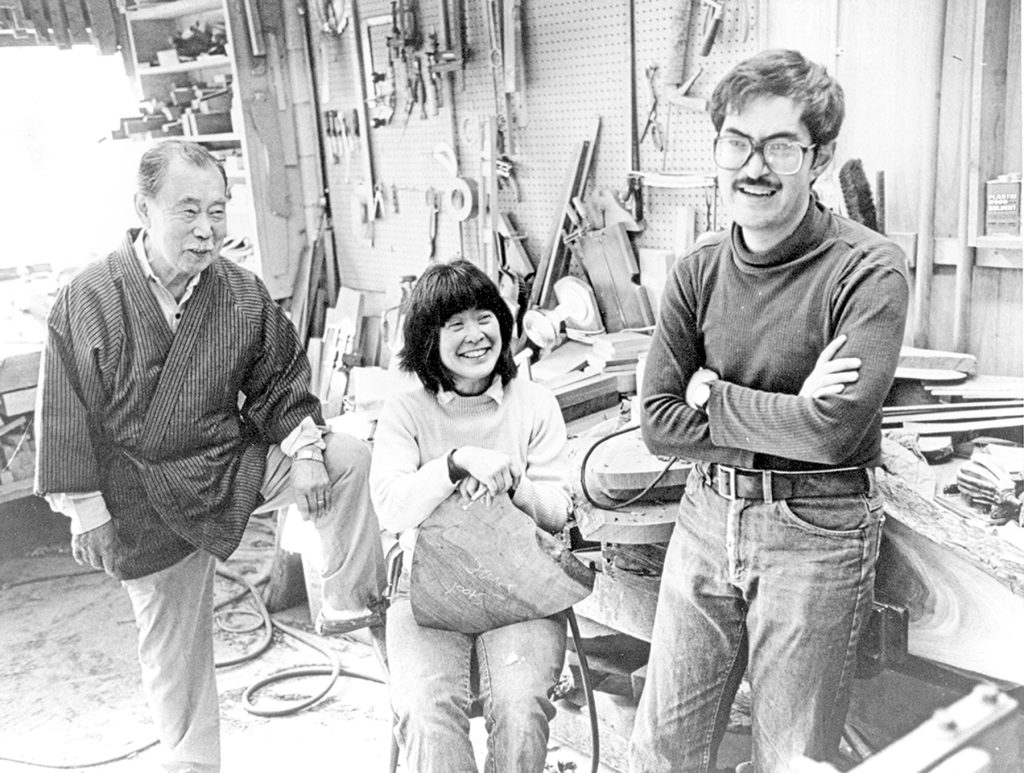

George, Mira and Kevin in the 1980s

My godmother, Milly Johnstone, knew me since I was 2 years old and made sure that I enjoyed plenty of tennis and swimming growing up. She took me to Japan in the fall of 1963 as part of a Zen Buddhism tour with Alan Watts (an influential religious philosopher who popularized Eastern religions, especially Zen Buddhism).

Then, I decided to live with my mother’s older sister, Thelma, in Tokyo to study Japanese. While I had two years of Japanese as an undergrad, I wanted to really learn the language. During that time, my dad contacted a former work colleague, John Minami, a Kibei who was teaching engineering at Waseda University. He made it possible for me to enroll in the master’s program.

Tsuitate Sofa

The Japanese system was so different: In the “atelier” system, we graduate students worked part-time on actual projects, not just drawings. We worked on really interesting projects, including the Imperial Palace Music Hall with Kenji Imai (a noted architect who embraced Antonio Gaudi’s architectural style).

Almost all of my classmates were men, and they were very kind. I met and married one of them, Tetsu Amagasu. While a graduate student, I was climbing scaffolding while pregnant and, after my son, Satoru, was born, I dragged him to class with me. I graduated in 1966. At that time, Dad was building the Katsura Catholic Church in Kyoto, so my then-husband and I worked on that project and learned a lot about construction first-hand.

Murase: How would you describe your style, first, as an echo of your father’s, and second, as distinct from your father’s?

Nakashima: Dad spent a lot of time in Japan. His parents were old-fashioned. Grandmother was in the court of the Meiji Emperor. Grandfather had a degree from Keio University. Dad’s family lived in Kamata in a beautiful farmhouse where they practiced and respected Japanese traditions. He worked in the Tokyo office of Antonin Raymond in the 1930s, where he met Junzo Yoshimura (later celebrated for his modern interpretation of classical Japanese architectural styles), who took him around to all of the best architecture in Kyoto. Decades later, my godmother, Aunt Milly, and I visited the same places on our tour of Buddhism in Kyoto. The architectural inspiration was the same for Dad and me.

Original Nakashima sketches detailing his design process (Photo: Courtesy of the George Nakashima Foundation for Peace)

Dad was old-fashioned. I was raised to do as I was told and not to question his authority. After I started working with him full-time, I got fired at least two times!

The work we did for the Krosnick family was a bridge between me and my father. Arthur and Evelyn Krosnick furnished their entire home with Dad’s work (112 pieces), but the home completely burnt down in 1989. Dad was in the process of replacing furnishings for their rebuilt home when he died. After I took over the business, Mrs. Krosnick encouraged me to create new and different designs.

Murase: In your career, what are you most proud of?

Nakashima: I am most proud of keeping the business going after my dad died. I had to fight my way out of the bag. While he was alive, Dad got all the publicity and attention, Mom handled all of the business. I began working with Dad full-time in 1970, and I worked alongside him until his death in 1990. When he died, everyone assumed that the business would close. Even the priest at Dad’s funeral in New Hope said the woodworking saws would fall silent, but I had other plans.

Simon Coffee Table

With the help of publicist Linda Milanese of the Michener Museum, I designed a room in tribute to Dad. This got a lot of attention and helped restore the business.

Murase: Tell me about your woodworkers.

Nakashima: We have a really wonderful crew. General Manager John Lutz has been with us for over 16 years. He came to us from Thomas Moser (handmade American furniture) with a degree from the Rochester Institute of Technology Furniture Design program. Before John arrived, I was having a terrible time. I was working on the Krosnick job, and everything kept changing.

John created a lot of structure and made sure that the woodworkers were training and training each other. The previous tradition was to keep your craft to yourself, but now, the older woodworkers are teaching younger woodworkers.

Co-foreman Alyssa Francis has been with us for 26 years. She was the first woman to be hired for the shop and has made almost everything we produce. Co-foreman Michael Veith has a Quaker background and previously worked in landscaping. Head finisher Justin Taylor has been with us for 20 years. Everyone has a different background. My husband, Jonathan Yarnall, has been working on chairs for 50 years, hand shaving individual spindles and assembling our chairs.

Murase: Tell me about your family and their role in the Nakashima legacy.

Nakashima: My grandson, Toshi, is helping with the family business. He is an extrovert, like his father, Satoru, and my late brother, Kevin. My daughter-in-law, Soomi, handles public relations and sales for the business.

Mira and Kevin

Murase: What was challenging about writing “The Nakashima Process Book”?

Nakashima: For the book, I needed to verbalize what I do naturally. I had to think about the craft of woodworking. I had to try to understand the spirit of woodworking as reflected in my father’s book “The Soul of the Tree.”

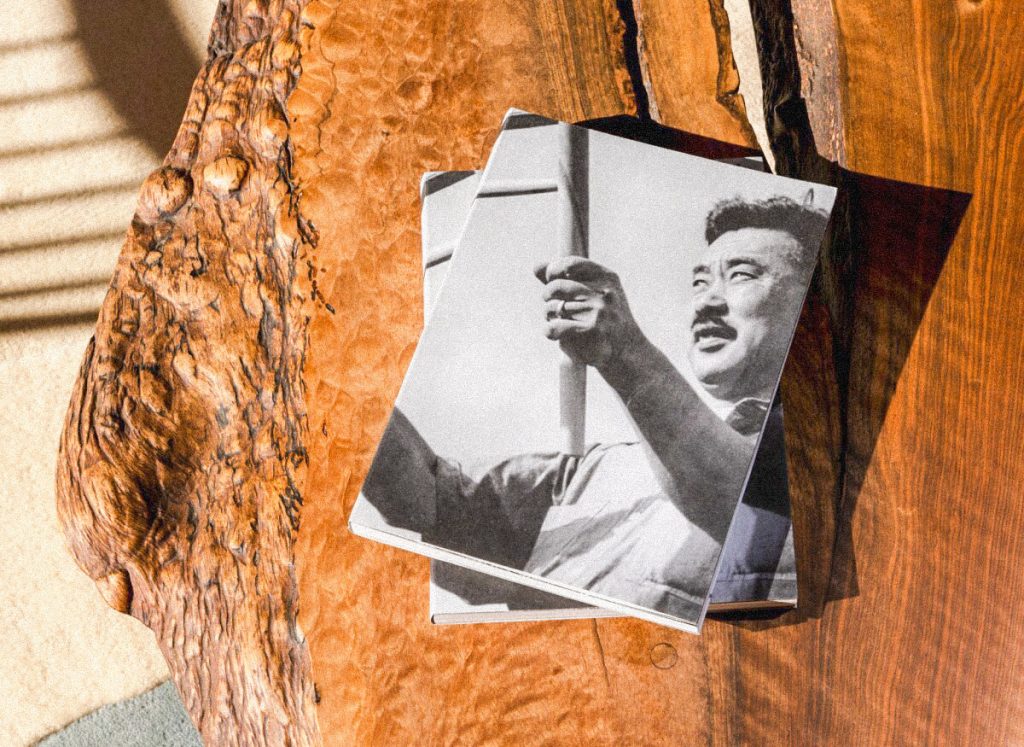

The “Nakashima Process Book” is a look inside the celebrated woodworker’s philosophy of furniture making.

I also spent a great deal of time designing the book. I wanted it to be a craft piece. The cover is a removable poster of my Dad on one side, his sketches on the other. The book is printed and hand sewn in Italy.

Murase: In a final message from Mira Nakashima — A special note is included in each copy of the book: “We invite you to become part of this ongoing process, a process we hope will continue as long as trees and people inhabit the earth.”

The “Nakashima Process Book” can be purchased at https://nakashimawoodworkers.com/.

Individuals and groups can tour the Nakashima Woodworkers Studio, located in New Hope, Pa., about an hour away from Philadelphia. Although all tours are sold out through October, Nakashima has afforded JACLers planning to attend the 2024 National Convention in Philadelphia a very special opportunity to visit the Nakashima Woodworkers Studio on July 9.

The two-hour tour is scheduled for 1 p.m. and will cover the Conoid Studio, Chair Shop, Showroom, Reception House, Arts Building, Lumber Shed, Pole Barn and Finishing Room (subject to change).

To register for the tour, please complete the form available at https://bit.ly/sfjacl_nakashima_tour.