How the Japanese American community stopped an auction and drew closer together

By Ray Locker

During World War II, art curator Allen Hendershott Eaton solicited artwork from prisoners in the 10 Japanese American concentration camps around the country and planned to exhibit the art around the country.

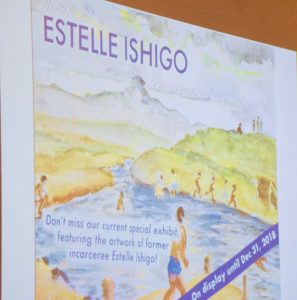

The artwork of Estelle Ishigo was featured in a special exhibit at Heart Mountain in 2018. (Photo: JANM)

One artist was Estelle Ishigo of Heart Mountain, Wyo., who corresponded regularly with Eaton and sent him some of the paintings and sketches she created while incarcerated. Ishigo had hoped her collaboration with Eaton, who worked in New York for the Russell Sage Foundation, would help her get a job once Heart Mountain closed.

Although Eaton published a book in 1952 about the art — “Beauty Behind Barbed Wire” — he never pulled off the exhibition. His daughter, Martha, inherited his collection when he died in 1962. She then gave pieces to contractor John Ryan in exchange for his work repairing her home after a fire, and then she willed the rest to Ryan upon her death in 1990.

Thomas Ryan left the art to his son John, who had no real attachment to it. John Ryan hired Rago Auctions of Lambertville, N.J., to sell it for him, and Rago announced its plans in March 2015.

That auction galvanized the Japanese American community and led to a new cooperation and activism that remains strong, according to a presentation held on Aug. 29 at the national convention of the American Association for State and Local History in Philadelphia.

JANM’s Clement Hanami worked within JANM to build opposition to Rago Arts’ intention to auction Japanese American artwork created during World War II. (Photo: JANM)

Clement Hanami of the Japanese American National Museum, Shirley Ann Higuchi of the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation and Nancy Ukai of 50 Objects Nikkei said the March 2015 announcement by Rago Auction House of New Jersey caught them by surprise.

When they learned of the auction, Hanami, Higuchi and Ukai said they separately concluded that the auction had to be stopped.

Hanami worked within JANM to build opposition to the auction and try to get the artwork at the museum. Higuchi mobilized her foundation’s board to fund legal action to stop the auction. Ukai mobilized a social media campaign that featured a Not for Sale page on Facebook.

“If we don’t say anything,” Ukai said of her feelings at the time, “nobody else will.”

Although the art was appraised for only $26,000, Heart Mountain offered Ryan $50,000 for the collection.

“I wanted to make them an offer they couldn’t refuse,” Higuchi said, knowing that the refusal of such a generous offer would show a lack of good faith on the seller’s part.

The three groups realized that the fight over the artwork brought together disparate elements of the Japanese American community that remained separated as part of the legacy of the WWII incarceration.

Chair by Yorozu Homma at Heart Mountain (Photo: JANM)

Hanami and Ukai said the legal action brought by the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation stopped the Rago auction in its tracks. JANM bought the artwork from Ryan and now has it as part of the museum’s collection.

One new development, Hanami said, is that the museum has an agreement with Heart Mountain for joint custody of the art created by Ishigo, a Caucasian artist who was incarcerated with her Japanese American husband. Ishigo’s art appeared in a special exhibit at Heart Mountain last year.

“We felt that Estelle’s artwork needed to be at Heart Mountain,” Higuchi said. “Her last wish was that her ashes be spread there.”

A New Collaboration

The Japanese American Confinement Sites Consortium exists “today because of this work,” Hanami said. “There is a sense of collaboration. That’s one of the great things to come of this.”

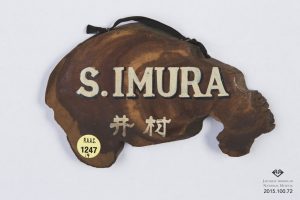

S. Imura sign at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles (Photo: JANM)

The consortium was created in 2016 to continue the cooperation that started during the auction fight. Its members meet annually in Washington to push for funding of the Japanese American Confinement Sites program, which is run by the National Park Service.

In August, the JACS program announced $2.8 million in grants to pay for restoration projects at various sites around the country and media projects. Heart Mountain received the largest grant of this cycle — $424,700 to help restore the site’s root cellar.

The joint appearance at the AASLH conference was another sign of the increasing collaboration between Japanese American groups. All three panelists said they planned to do more appearances together with the hope of telling more stories behind the rescued artwork.