Remembering the Crystal City internment camp helps shed new light on the importance of building awareness today in order to preserve family histories and eliminate new social injustices.

By Alissa Hiraga, Contributor

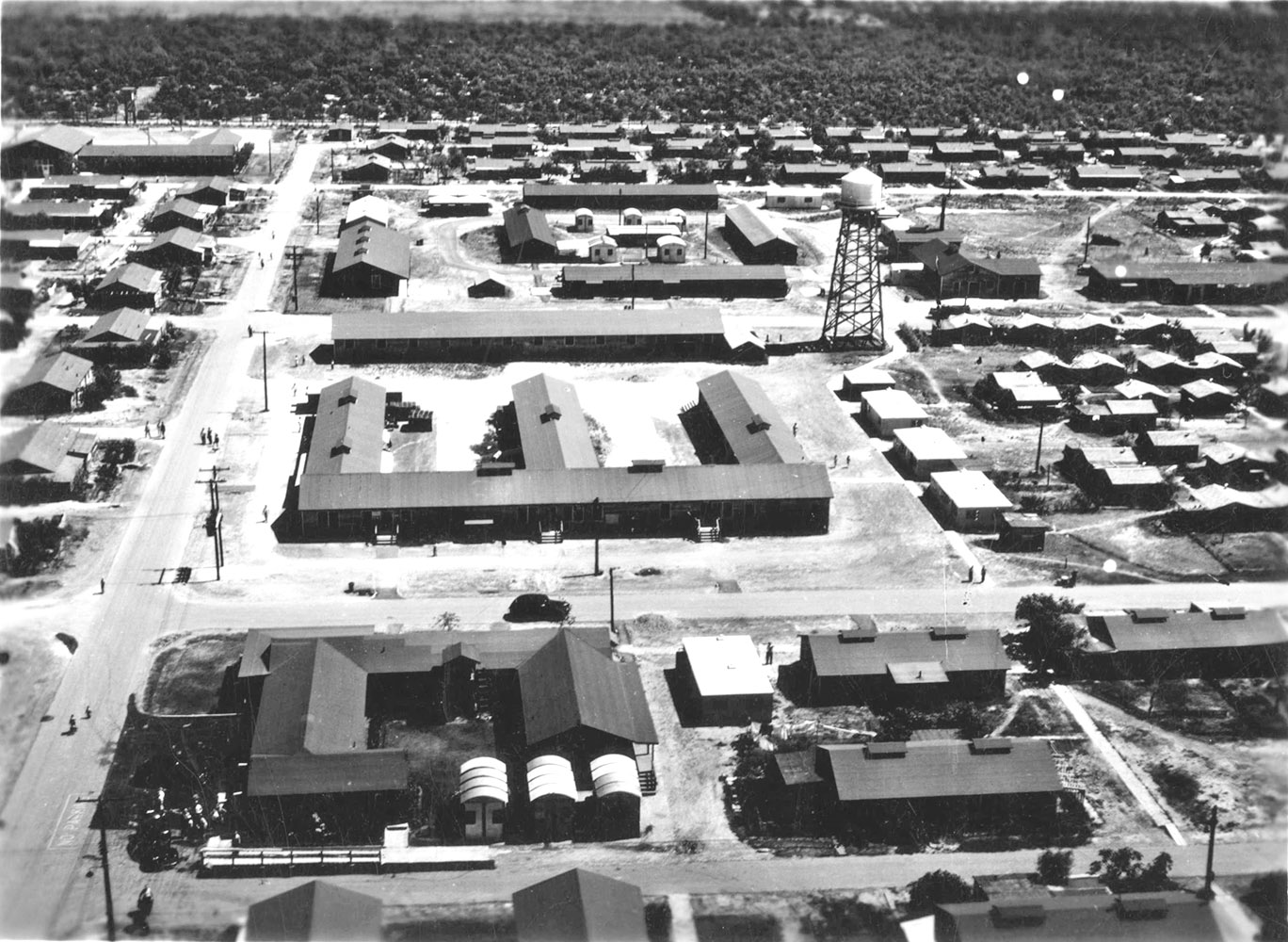

The story of the World War II internment camp in Crystal City, Texas, is unknown to many.

Yet, it was a fateful intersection of 4,000 souls robbed of their freedom — among them Japanese, Japanese Peruvians, Germans, Italians and Americans. The violation extended to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s prisoner exchange program, its machinations hidden from the general public. Those arrested, even U.S. citizens, were exchanged for the return of “valuable” U.S. citizens held overseas. Others would be deported or repatriated to their “home” countries.

The Crystal City internment camp was previously the site of a migrant worker housing camp. It was later repurposed and opened in 1942 by the Immigration and Naturalization Service to confine Issei men and “enemy aliens” that the War Relocation Authority branded as “troublemakers.”

The use of such a term helped make the justification to detain, interrogate and imprison innocent people more palatable. (By war’s end, not one Issei was found to have committed espionage or sabotage against the U.S.) The Issei targeted by the government included community leaders, physicians, journalists, activists, creative artists, writers, teachers and Buddhist priests.

The camp is often described as a “family camp,” as the Issei men were reunited with their families there. The camp was much less severe than the 10 WRA-operated American concentration camps such as Manzanar, Rohwer and Heart Mountain.

As a DOJ-designated camp for “enemy aliens,” Crystal City was required to abide by the Geneva Convention. Under the treaty requirements, internees lived in family units with kitchens and bathrooms. The camp had the elements of a typical town, its landscape dotted with schools, stores and a swimming pool.

Lane Hirabayashi, professor of Asian American Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the inaugural George & Sakaye Aratani Chair in Japanese American Incarceration, Redress and Community, believes that understanding the differences between the WRA camps and the DOJ camps is essential for informative, accurate discourse on internee’s experiences.

“If we educate our readers, our students and even members of our Japanese American communities about this, then we are contributing to a better understanding of the penal policies that the U.S. government has adapted in the past in response to perceived crises and national security threats,” Hirabayashi said.

Resources such as the JACL’s “Power of Words Handbook: A Guide to Language About Japanese Americans in World War II” serves as an educational tool to help accomplish these important objectives.

Crystal City closed in 1948, but it marked the beginning of struggles for families leaving the camp. The Japanese Peruvians were not allowed to stay in the U.S. or return to Peru and would engage in an exhaustive legal fight to salvage their futures.

Those who returned to Japan and others who sought to rebuild their lives in the U.S. endured treacherous journeys or entered a world unknown or unwelcoming to them. The journeys to and from Crystal City that families were forced to take at times had tragic outcomes.

Brian Niiya, content director of Densho Encyclopedia and editor of “Encyclopedia of Japanese American History: An A-to-Z Reference,” shares the story of his family.

His mother, Alice Asami, and seven of her family members were interned at Crystal City in 1943 prior to being repatriated to Japan on the second voyage of the MS Gripsholm. Niiya’s grandfather, Shoichi Asami, was managing editor of Nippu Jiji newspaper in Honolulu.

“My mom had largely fond memories of Crystal City because it was the last time their whole family was together,” Niiya recalled. “After her father was interned on Pearl Harbor day, the family had a difficult time in Hawaii, and she remembers living conditions there as being pretty good, especially compared with what they had to endure later. But theirs was certainly not the typical experience or reaction.”

Shoichi and his son, Harold, died in 1945 on the Awa Maru after torpedoes from the USS Queenfish attack submarine killed all but one of the ship’s 2,004 passengers. The Asami family’s story is chronicled in “Our House Divided: Seven Japanese American Families in World War II” by Tomi Kaizawa Knaefler.

The Crystal City internees who began to rebuild their lives faced another tribulation. The false “troublemaker” label attached to the Crystal City camp is a punishing stigma that still haunts many Crystal City internees today. It was a label born from a chilling assumption of racial guilt rather than any military or other intelligence.

“Although there was a great deal of paranoia about the Issei and Kibei, and despite the fact that these special DOJ camps were set up to incarcerate them specifically, after the end of the war not a single person was successfully prosecuted and convicted of a crime related to sabotage and espionage,” said Hirabayashi. “So, the so-called stigma of being in a DOJ camp like Crystal City is really based on a twisted notion of ‘guilt by reason of race.’ Not on any actual evidence of pro-Japan, anti-U.S. activity.”

In his discussions with many Hawaii internee families, Niiya found that some were shut out from their own communities.

“Whereas all Japanese Americans living on the West Coast were thrown into camps, it was only a select group that went to places like Crystal City; therefore, regardless of the reason people were there, the idea that they were in a ‘special’ camp led to rumors that they must be guilty of something. In Hawaii, internee families also talk about how former friends and acquaintances shunned them out of fear that associating with them would lead the FBI and Army to target them as well.”

The families who lived and endured behind Crystal City’s barbed wires and under the watchful eyes of armed guards possess a myriad of precious stories.

An Utsushigawa family photo featuring Sumi (center) and her two sisters, along with their parents, Tokiji and Nobu.

Many of these stories have been painstakingly captured and preserved to the credit of Sumi (Utsushigawa) Shimatsu and her daughter, Paula Shimatsu, who affectionately refers to the Crystal City families as her “aunties” and “uncles.”

Sumi, her mother, Nobu, and her father, Tokiji, were interned at Crystal City. Before the war, life in Los Angeles was described as idyllic for the Utsushigawa family. Tokiji was the first Japanese photographer in Los Angeles. The family lived in an apartment above the Mikawaya confectionary and was part of a close-knit community. That life was forever altered after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

In high school at the time, Sumi came home from school to discover that her father had been arrested without charges and taken away by the FBI. In a grueling odyssey, the family was separated, with Tokiji incarcerated in Santa Fe, N.M., and Sumi and Nobu detained at the Pomona Assembly Center. They were placed on a train to the Heart Mountain concentration camp in Wyoming. After Heart Mountain, Sumi and Nobu were sent to the Port of New Jersey to await repatriation to Japan as part of the prisoner exchange.

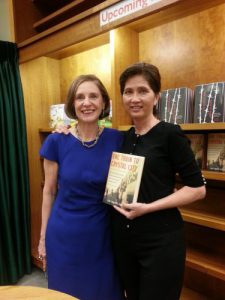

“The Train to Crystal City” author Jan Jarboe, left, with Paula Shimatsu.

“My father wrote that he was going to Japan on an exchange ship, so mother and I were escorted out to Montana camp; our baggages inspected, no printed articles, books or newspapers allowed and were sent to New Jersey Harbor. [We] saw the [MS Gripsholm] exchange ship but did not get on since there were too many people, like diplomats, to send back to Japan. [We] were sent to Ellis Island, stayed there four days, then took a train down to Crystal City with the camp head,” Sumi recalled. Her story is told in the book “The Train to Crystal City” by Jan Jarboe Russell.

After Crystal City, Sumi returned to war-ravaged Japan with her family and worked at an American military base to help support her family. She eventually returned to the U.S. and finished high school. She later married Kiyo Shimatsu, who served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, and had six children. Sumi also created the Crystal City Chatter, a newsletter she published to keep people connected. Her dedication with the Crystal City Chatter and the reunions gradually encouraged others to open up and share their stories.

For Paula, the gratitude she has for her parents for their ultimate triumph in building a loving home for their children only strengthened with time.

“No one assumed I was dumb or lazy because of how my parents raised me,” Paula Shimatsu said. “They gave us gifts to grow and develop, and enjoy a better life.”

Paula wanted to understand her mother and grandfather’s stories at a young age. The adults did not want to talk about their painful experiences during World War II. She decided to write her high school report on the Japanese American experience and spent weeks entrenched at the Los Angeles Public Library.

She was shocked to find the amount of literature about the internees, who were never a threat to the U.S. It was painful to learn about Japanese and Japanese Americans losing their homes, properties, lands, assets and businesses, while others benefited from their loss. People took notice of her knowledge and compassion for the subject matter. In high school, her sociology teacher asked her to teach the class on the experiences of the Japanese during World War II.

Paula, a University of California, Berkeley, graduate with an expansive background in the entertainment and corporate field, would over the years help internees preserve their experiences and personal artifacts, through oral histories to video and digital archiving. It has been her goal to ensure that anyone is able to share material and preserve the material in manner that is usable for all.

Paula was also invited to participate in a panel for a University of Southern California retrospective of the iconic TV show “Twin Peaks,” where she once worked as a unit publicist. She asked if the USC Library was interested in archiving all of her photos, negatives and documents from “Twin Peaks.” It was at this time that she suggested the material from the Crystal City camp families.

“Why not have material in different places? People can access material, create awareness and learning, and connect with one another,” Paula said.

She began working with Ken Klein, librarian at USC and head of the East Asian Library.

“Materials that can give details about the Crystal City camp are a particularly important set of records because so little attention has been paid to his episode of history. It lies somewhat outside of the also very important but better-known history of Japanese American ‘relocation camps,’ and does fit so neatly into that narrative. This is why we were so interested when Paula contacted us with the prospect of hosting records from some of the Crystal City camp families,” Klein said. “From the beginning, she has told of her concern that this history be preserved while some of the former residents are still alive and able to relate their experiences. Paula clearly feels a great responsibility to see her mother’s and others’ life stories are preserved, and she has been dogged in this effort, even through some personal hardships and setbacks. This, in turn, increases my own sense of responsibility to do as much as I can to help further this effort.”

Niiya believes historical preservation efforts are valuable and necessary for many reasons.

“On a micro level, all of us have our own family stories and histories. Is anyone taking the initiative to document these? Whether through oral history interviews, organizing and digitizing of family documents and photographs, or other means, it is important that someone does. Even if no one is interested now, it is highly likely that someone — a child now, or maybe someone who hasn’t even been born yet — will eventually, and that person will be eternally grateful for the work we can do now,” Niiya said. “On a macro level, support organizations that do this kind of work, whether national organizations like Densho or local ones, whether as a volunteer, donor or user. As recent events have shown us, we have an important story to tell and a responsibility to tell it.”

Today, incendiary and false information is on the rise, and historical aspects can be distorted by those who seek to serve hateful ideologies. The resurrection of past injustices driven by fear and racism is not a far off reality. Building awareness is more critical than ever.

“The more people involved in the preservation of history, the more people who can be reached and affected by what happened. And that hopefully leads to more people being committed to never letting it happen again, which is a core principle of our work,” said Ann Burroughs, interim president and CEO of the Japanese American National Museum.

Said Hirabayashi, “It is exactly in the process of recounting and preserving the personal stories of the individuals and families that suffered from their imprisonment on the basis of race that we can convey to the public exactly what the price of a very flawed public policy can be on the psyches and lives of those subject to harsh, unjust treatment.”

Note:

JACL’s “Power of Words Handbook: A Guide to Language About Japanese Americans in World War II” is available at https://jacl.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Power-of-Words-Rev.-Term.-Handbook.pdf.

For those interested in adding records related to Crystal City or any aspects of Asian or Asian American history, please contact Ken Klein at East Asian Library, USC Libraries, at kklein@usc.edu or call (213) 740-1772.