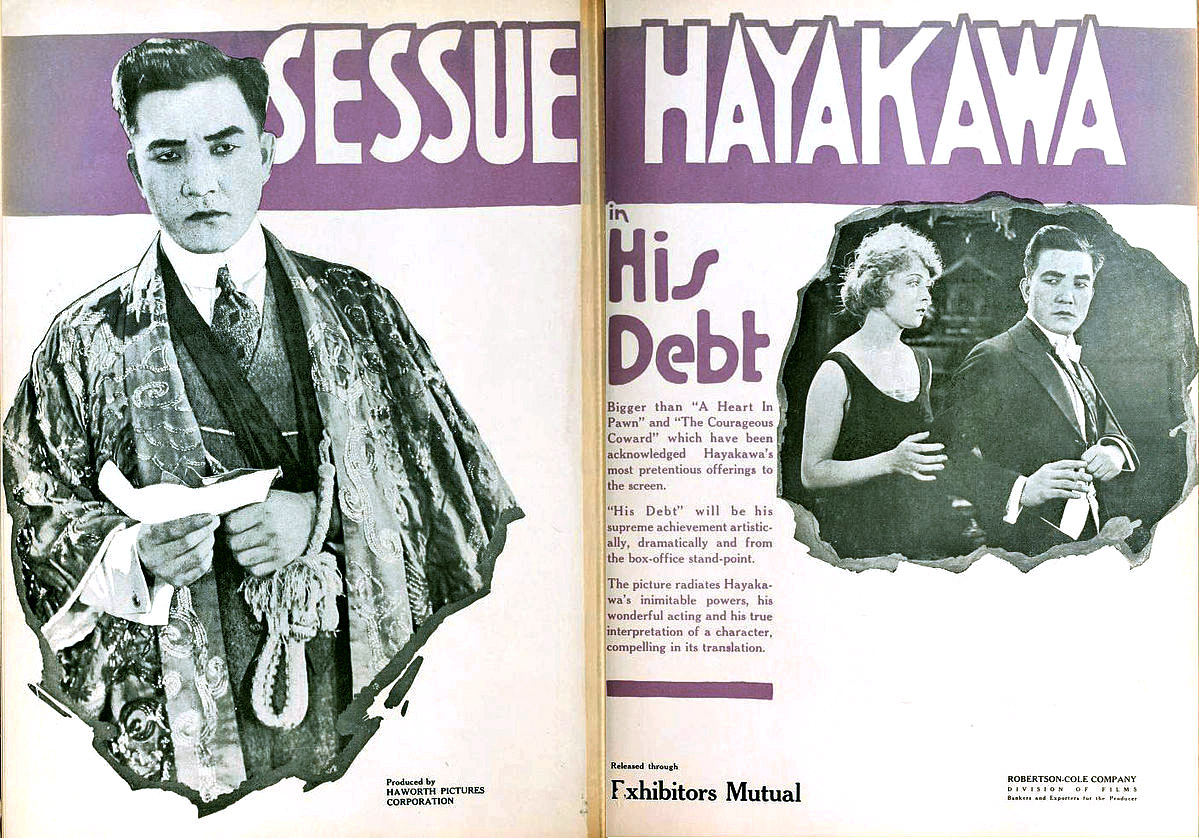

Sessue Hayakawa starred in 1919’s ”His Debt,” which was produced by his Haworth Pictures Corp.

Early Asian American actors persevered to make a name for themselves in a film world dominated by their Caucasian counterparts.

By Rob Buscher, Contributor

It would shock many film buffs and casual viewers alike to learn that there was a time in early Hollywood cinema when several Asian Americans were among the top A-list celebrities.

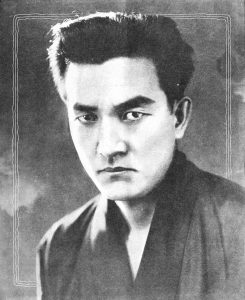

In fact, one of the highest-paid actors in 1910s Hollywood was a Japanese immigrant named Sessue Hayakawa. Hayakawa would go on to become the first (and to this day only) Asian American to own a Hollywood studio, which netted more than $2 million in profits at the height of its popularity in the late 1910s.

Born in 1889 as Kintaro Hayakawa in Chiba Prefecture, he emigrated to the United States to pursue a degree in political economics at the University of Chicago. After flunking out of school, Hayakawa’s plan to return home became waylaid when he caught a theater performance in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo — he fell in love with the stage.

Hayakawa became a regular player at the Japanese Playhouse in Little Tokyo, where he was discovered by Hollywood film producer Thomas H. Ince. Against all odds, Ince agreed to pay him the extraordinary sum of $500 per week to star in the silent film adaption of a stage play called “The Typhoon” in 1914.

“The Typhoon” starred Hayakawa as a Japanese diplomat to France who, after having an affair with a chorus girl, strangles her to death in a fit of passion. Despite the negative stereotyping of his character, Hayakawa’s brooding good looks made him an undeniable sex symbol amongst white women across America.

Cast in a similar role the following year by legendary director Cecil B. DeMille, Hayakawa shared the first-ever onscreen interracial kiss with a white woman in the 1915 film “The Cheat.”

Although the studio took a substantial risk by visually suggesting miscegenation, it still made him the villain by making his character brand his lover with a hot iron after she tries to break off their affair.

Asked about the significance of Hayakawa’s sex-symbol status, Center for Asian American Media (CAAM) Executive Director Stephen Gong said, “I think [Hayakawa’s] transgressive stardom (white women being his primary — and ardently loyal fan base) served as a cautionary tale for the developing industry and its concomitant censorship-machinery. Rudolf Valentino, in the 1920s, elicited a similar ‘forbidden’ fan response, and that from a very light-complexioned Italian. I think the industry was quietly but completely determined not to allow Asians or nonwhites to become ‘stars.’ ”

Fed up with the self-proclaimed Orientalist roles that he was being cast in by the major Hollywood studios, Hayakawa decided to go out on his own by founding Haworth Pictures Corp., where he subsequently released 19 films between the years 1918-22.

Gong elaborated on Hayakawa’s tenuous relationship with race in Hollywood.

“I think at the time he was working, all filmmakers were using stereotypes as tools of the trade to get people to watch, and hopefully pay a few cents for the pleasure,” he said. “I don’t think many people were thinking critically about authentic cultural or ethnic representation before the 1960s or 1970s. That said, Hayakawa was aware of the racism behind his character in ‘The Cheat’ and was determined therefore to play the hero in his own Haworth and Hayakawa Feature Play films — albeit many of those employed stereotypical depictions of Chinese, Mexicans, Indians and others.”

Alas, the rising anti-Japanese sentiment in early 1920s California made Hayakawa unpalatable to Hollywood moguls looking to cash in on their majority white audience. Hayakawa spent the next decade working in Europe, and by the time he returned to Hollywood in the 1930s, his thick Japanese accent pigeonholed him as a character actor in the new talkie era.

Hayakawa’s return to Hollywood coincided with the rise of another Asian American star — Anna May Wong, who coincidentally had a starring role in Hayakawa’s 1931 sound debut “Daughter of the Dragon.”

The American-born daughter of Chinatown laundry owners, Wong holds a special place in film history as the first Asian American actress to become a major Hollywood sensation.

“Anna May was fascinated by film from a very early age … She played hooky from school to watch movies and sometimes snuck into shoots on the streets of Chinatown. From those humble beginnings, she rose to prominence against great odds and paved the way for the current generation of Asian film actors to make their mark,” said filmmaker Peilin Kuo, who is an authority on Wong.

The majority of films featuring Wong were released after the Motion Picture Production Code went into effect in 1930. Better known as the Hay’s Code after President Will H. Hays of the Motion Picture Association of America, this agreement amongst executives from each major Hollywood studio outlined what should and should not be permitted onscreen. With anti-miscegenation laws active in California until 1948, this prevented Wong from taking on roles that involved romance with a white male lead.

“During her Hollywood career, [Wong] suffered from the frequent stereotyping of Asian women as ‘China dolls’ or ‘Dragon ladies.’ Despite her prodigious talent and screen presence, she was usually relegated to playing secondary roles to white actresses,” Kuo said. “The closest she came to a lead Asian role in a major studio film was in ‘The Good Earth’ (1937), but she lost the role to Luise Rainer, a white actress in yellowface, who won an Oscar for the role.”

By the 1930s, romantic Asian male leads were virtually nonexistent, and when the script called for one, Hollywood frequently cast white men in yellowface. Even in these cases when a white actor was portraying an Asian onscreen, interracial relations were forbidden, thus preventing Wong from landing these roles.

A rare exception is the 1937 thriller “Daughter of Shanghai,” in which Wong starred opposite of Korean American actor Philip Ahn as the daughter of a wealthy Chinese merchant who goes undercover as a nightclub dancer to try and expose the illegal human-trafficking operation that led to her father’s death.

Despite the potential for onscreen romance with Ahn, the couple barely holds hands, let alone kisses, before she agrees to marry him in the closing scene, suggesting perhaps that even onscreen romance between two Asians was deemed inappropriate by Hollywood tastemakers.

Reflecting on her own relationship to Wong’s work, Kuo said, “As an Asian woman myself, I related to her struggle as a person caught between East and West. Even though she was born in a different time, I was so inspired by her strength, her will to fight, her persistence to fulfill her dream. Although Anna May was the biggest Asian American movie star during her career, that career was limited by prejudice and the star system. Nowadays, she is often held up as an object lesson of a major talent whose career was thwarted by discrimination in Hollywood. In a real sense, her career hovers over today’s conversation about the underrepresentation of women and Asians in major Hollywood films.”

Another familiar Asian face in 1930s-40s cinema was Sabu Dastagir, known by audiences simply as Sabu. An Indian national, Sabu began his career in cinema at the young age of 13, when he was cast in the titular role of Robert Flaherty’s 1937 film “Elephant Boy.”

Based on an adaptation of the Rudyard Kipling novel “Toomai of the Elephants,” the film would set the tone for most of Sabu’s career as a comical sidekick whose image would become inextricably linked with the orientalist fantasy embodied in Kipling’s work.

“In the following years while living in England, the adolescent boy starred in glorifications of the British Crown, appeared in fantasies inspired by Arabian Nights’ Orients and was featured in Rudyard Kipling adaptations that sensationalized Sabu as a ‘real’ jungle boy in the press,” said performance studies scholar Jyoti Argadé. “Often playing a ‘sidekick’ to the white hero, he appeared as an affable savage child or an effete prince who was powerless before British colonial authority. Many a time he portrayed what could be termed ‘Orientalist stereotypes.’ ”

Sabu earned his first shot at Hollywood when the outbreak of WWII forced London Films to relocate production to California while shooting 1940’s “The Thief of Bagdad,” a remake of an earlier 1924 film that coincidentally starred Wong in a minor role.

In this film, Sabu played one of his more valiant roles, albeit race-bending as an Arab, beginning the story as a humble street beggar who, after vanquishing a genie and completing a series of trials, becomes the Prince of Thieves. Achieving success with “The Thief of Bagdad,” London Films’ follow-up picture also shot in Hollywood and starred Sabu as Mowgli in the original 1942 live-action adaptation of Kipling’s “The Jungle Book.”

Sabu’s best-known roles in American cinema were perhaps his most problematic, in which he starred after signing a three-film contract with Universal Pictures. Part of a larger trend of wartime escapism in Hollywood, Universal marketed these titles as “exotic films” known for their far-flung locales, action-packed plots and scantily-clad women.

Together with Jon Hall and Maria Montez, Sabu starred in 1942’s “Arabian Nights,” 1943’s “White Savage” and 1944’s “Cobra Woman.” Sabu adopted a subservient comic relief role in each film and race-bends as either Arab or Pacific Islander; meanwhile, his counterparts were highlighted as the romantic leads. Although Montez as a Dominican and Hall, who was half-Tahitian, were of different races, they were allowed to star onscreen as lovers, perhaps because neither was technically white.

While there are no documented remarks from Sabu showing criticism of his relegation to subordinate roles, his choice to enlist in the U.S. military and subsequent naturalization as a U.S. citizen suggests that he was actively seeking to elevate his position in American society.

From 1943-45, Sabu flew more than 30 missions as a ball-gunner in the 13th Army Air Force’s famous Lone Ranger bomber group and became one of Hollywood’s most-decorated war heroes.

Unfortunately, upon returning to Hollywood, Sabu’s attempts to regain his wartime stardom were unsuccessful.

“When Sabu returned from the war, the caliber of his roles began to dwindle,” said Argadé. “He no longer headlined as the lead. Once Hollywood studios began to replace the 1930s genre of ‘exotic’ adventures with movies more inclined toward post-WWII social realism, Sabu’s career as an ‘exotic’ in fantasy films diminished.”

While circumstances differ between Hayakawa, Wong and Sabu, each of their careers came to a premature end. Had they been given the opportunities of their white counterparts, one wonders if film studies might remember Hayakawa alongside Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks or consider Wong as a true contemporary to Joan Crawford and Ginger Rogers.

The very fact that their stories exist counters the perpetual foreigner myth by proving that Asians have lived in and contributed to the culture of the United States long before the Immigration Act of 1965.

Despite personal tragedies in their careers, each of these actors left an important mark as early forbearers to the Asian American movement.

“Given his background and personality, I don’t think he was conscious of the need for an Asian American film movement,” said Gong on Hayakawa’s legacy. “He famously said early on that he was determined to make films in American for Americans. But I think people can take something from his story and his pride and ambition and assert that it was an important and early chapter in Asian American media history.”

Unfortunately, prevalent institutional racism in Hollywood has prevented these talents from being remembered as anything but an anomaly in the history of cinema. Likely, there are many others whose names and stories have also been lost to time.

In an effort to counter the narrative of erasure, the Philadelphia Asian American Film Festival (PAAFF) has embarked on a project to resurface and preserve the cultural memories of the Asian American actors who paved the way during the early years of Hollywood.

Sponsored in part by the JACL Legacy Fund, the 2017 PAAFF will feature a retrospective of significant films starring AAPIs throughout the history of early Hollywood cinema, taking place between Nov. 9-19 in Philadelphia.

Screening times and venues will be announced on PAAFF’s website later this fall, but the retrospective will feature films starring Ahn, Hayakawa, Sabu and Wong.

For more information, visit www.paaff.org.