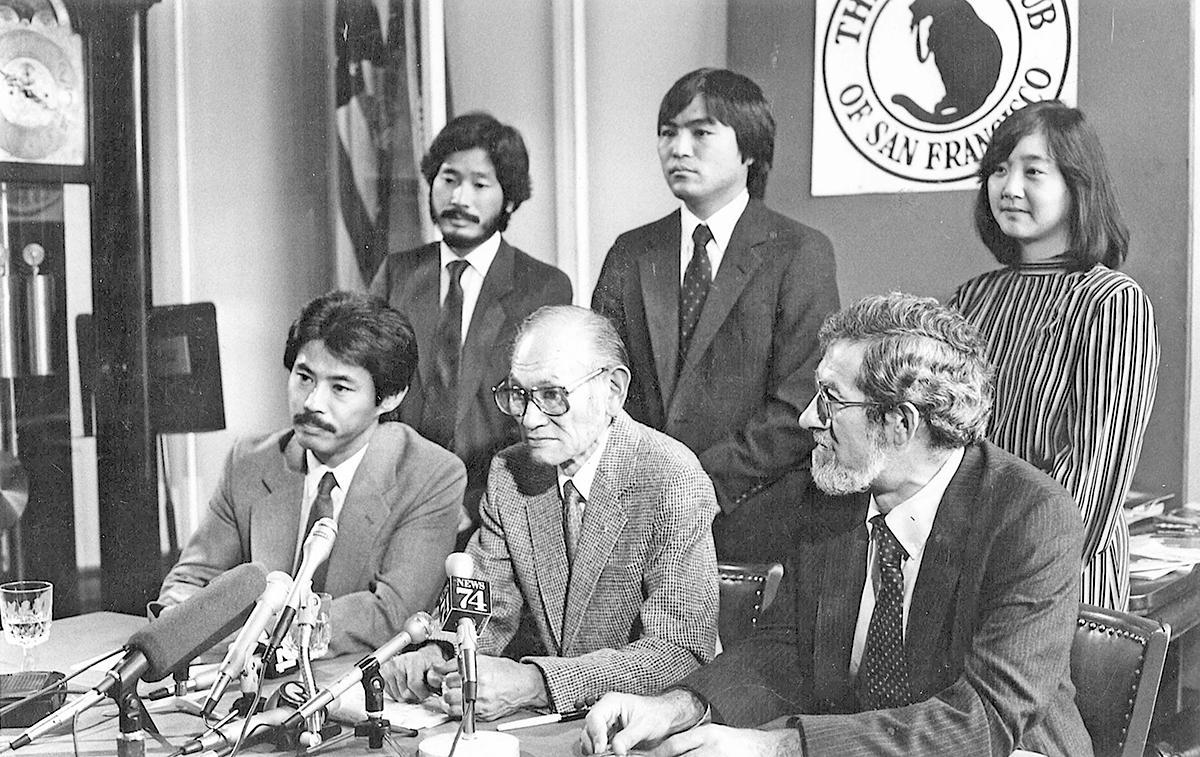

Gordon Hirabayashi (center) and members of his legal team. Pictured (back row, from left) are

Rod Kawakami, Michael Leong and Benson Wong and (front row, from left) Arthur Barnett and Kathryn Bannai. (Photo: Michael Yamashita)

Two of the three coram nobis cases were led by Sansei women.

By Lynda Lin Grigsby, P.C. Contributor

Peggy Nagae was lead counsel for Min Yasui. (Photos: Courtesy of Peggy Nagae)

The day before she was set to present her argument in what she called “the case of a lifetime,” Peggy Nagae convinced a clerk to let her in an empty courtroom so she could practice. The Portland, Ore.-born farm-girl-turned lawyer always had a way with words, but in the courtroom, everything mattered. She worked on her tone, pacing and delivery.

“And it was good,” said Karen Kai, a legal team member who was there to help her prepare.

In 1984, Nagae’s strong performance was critical. A lot was at stake for her client, Min Yasui, who, armed with new evidence, had one more chance to exonerate himself of his wartime conviction. It was Yasui’s coram nobis case. Nagae was his lead counsel.

To play the role in court, she had to be assertive. That wasn’t a problem.

When Nagae left the courtroom, she had to shed skin in favor of a softer version that felt more acceptable in the Japanese American community. Her father, Shigenari Nagae, was a Gresham-Troutdale JACL chapter president. In the community, she was always “Shig’s daughter.”

The constant shifting of behavior, speech and appearance to put others at ease — or code-switching — felt impossible at times. Nagae once confided in Dr. Hideko Bannai, then a Nisei professor in the master’s program at the University of Southern California. Dr. Bannai urged her to consider it a character-builder. Code-switching is a skill that gives a person the chameleonlike ability to move through many social and professional situations.

Nagae agreed, but she quietly wondered if a man in the Japanese American community would have to constantly wrestle with being “Shig’s son”?

Cultural mores or the rules for socially appropriate behavior are “more caught than taught,” said Nagae, 72, a Portland JACL member. For women, these principles can be set in reproachful silence, a withering stare or questions like, “Why can’t you be nicer?”

To fit into the Japanese American community, Nagae turned up the politeness, softened her edges and downplayed her successes until the outline of her body of work began to fade. This isn’t unusual for people of color, who are three times more likely to code-switch in the workplace, according to a recent survey published on Indeed.com.

Peggy Nagae

Nagae and the women who led and worked on the coram nobis cases face a unique obstacle — erasure from the historical narrative.

“For many decades, people did not even know I was one of the lead attorneys,” said Nagae, about her role in the Yasui case.

Over the years, she had felt many feelings: Erased.

Dismissed. Devalued.

“[It’s] as though the Yasui case didn’t even exist.”

‘We’re Alive. You Can Talk to Us.’

The faces of the legal fight against the World War II incarceration were Yasui, Gordon Hirabayashi and Fred Korematsu — three larger-than-life Nisei men who cast large shadows with their individual stories of defiance.

Motivated by the simple desire to live their lives and the belief in their Constitutional rights, they resisted wartime curfew and forced removal orders. They fought — and, yes, lost — their legal cases in the Supreme Court.

About 40 years later, new evidence was discovered showing how government officials suppressed evidence during WWII to justify the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans. The discovery breathed new life into the cases. Lawyers for the Nisei men filed three separate writ of coram nobis petitions — starting with Korematsu — in three different states to seek exoneration.

Kathryn Bannai and her son, Jared, with the Hirabayashi legal team (Photo: Stan Shikuma)

Even though two of the three cases were led by Sansei women — Nagae and Kathryn Bannai, lead counsel for Hirabayashi — public perception has largely focused on the Korematsu case and core members of its legal team.

“I think they deserved more credit for their courage in taking these monumental cases,” said Dale Minami, the Korematsu case’s lead counsel, about the women who led the cases.

Their roles have been diminished, he added. But the reasons are complex and largely based on situational factors, said Minami. Korematsu is the most well-known of the coram nobis cases partly because it was first out of the gate in a press-friendly San Francisco market. It was the first victory — and the most publicized.

Members of Korematsu’s legal team. Pictured (back row, from left) are Dennis Hayashi, Lorraine Bannai, Donna Komure, Leigh-Ann Miyasato, Bob Rusky and (front row, from left) Don Tamaki, Peter Irons, Fred Korematsu, Karen Kai and Dale Minami. (Photo: Courtesy of Crystal Huie)

All three Nisei men’s wartime convictions were ultimately vacated. Over the years, he said, commentators, legal scholars and documentary filmmakers have fixated on Korematsu, the case, and its corresponding legal team.

“I know some folks feel overlooked, and I can understand why,” said Minami, 77, a Watsonville-Santa Cruz JACL member. “But in the context of the situation, I can also see why the press and the public ‘elevated’ the attention to Korematsu.”

If the Korematsu case is the most well-known of the three cases, then the large shadow it casts can also threaten to swallow the work of the women who worked on the legal teams. A 2019 San Francisco museum exhibit about the WWII incarceration attributed all three cases to the leadership of Minami and Don Tamaki, members of the Korematsu legal team.

Reporters and historians who seek to tell a historical narrative often cite the same experts for opinions. This can repeat in perpetuity until an association happens: When you think of the coram nobis cases, likely you think first of Korematsu. Then, Minami and Tamaki.

But teams of people worked together to push the cases across the finish line.

“We’re alive,” said Lorraine Bannai, who worked on the Korematsu legal team. “We’re here. You can talk to us.”

A Narrow Band of Appropriate Behavior

Yasui and Hirabayashi called upon Sansei women to lead their legal teams because they were the complete package, said Kai, 70, who worked with all three legal teams.

“They had the intellectual lawyer skills to absolutely do the job. But they also had this leadership ability,” said Kai. “They understood how to put together their cases and make things work.”

From 1982 to early 1985, Kathryn Bannai served as lead counsel in the Hirabayashi case. In a Seattle courtroom, she set the tone by defeating the government’s effort to dismiss the case. She also persuaded the court to grant a full evidentiary hearing.

She did this while five months pregnant.

It’s just something you just do as a woman, said Kathryn Bannai, 73. The full evidentiary hearing was scheduled a year later. She worked on the case until the day she gave birth. Then, she faced a dilemma many new parents without guaranteed childcare must consider — how to balance the demands of a career and a deeply personal case with the care of a baby.

She decided to step down as lead counsel.

Kathryn Bannai

“It was difficult,” said Kathryn Bannai, a New York JACL member, about the decision. “I think I could say — disappointing.”

This is the double bind of motherhood, especially in a country without a social safety net for new parents. Being a mother is a joy, she emphasized. But difficult decisions need to be made. After stepping down as lead counsel, she continued to work on the Hirabayashi case while also running her private law practice. Rodney Kawakami, who was also balancing his law practice while starting a family, took over as lead counsel.

Critical work for the Hirabayashi case was done at Kathryn Bannai’s Seattle law office during the evenings and weekends — outside a daycare’s normal business hours. To work on the Hirabayashi case, she would pick up her baby from daycare before closing time and bring him back to the office. At least once, the legal team gathered for a group photo for which baby Jared is front and center, jubilantly sitting on a table next to a copy of “Personal Justice Denied.”

Caretaking is something mothers do, but social expectations also give men more freedom to maneuver within the constraints.

Kathryn Bannai’s work is inextricable from the Hirabayashi case.

“Kathryn was our first fearless leader,” said Kawakami, 74. “She was responsible for assembling the team of attorneys and was the first public face of our case. Kathryn established the legal team’s credibility with the public and set the tone for how we would operate that continued after I took over.”

But in the case’s retelling, her role often gets diminished or omitted.

“The judicial record has been there all along,” said Kathryn Bannai. “The truth has been there all along.”

In 1987, a group of researchers theorized that for female leaders to succeed, they need to conform to a “narrow band of acceptable behavior,” which means they can’t be too feminine or overly masculine.

Add cultural mores to the mix, said Nagae, and the band gets narrower.

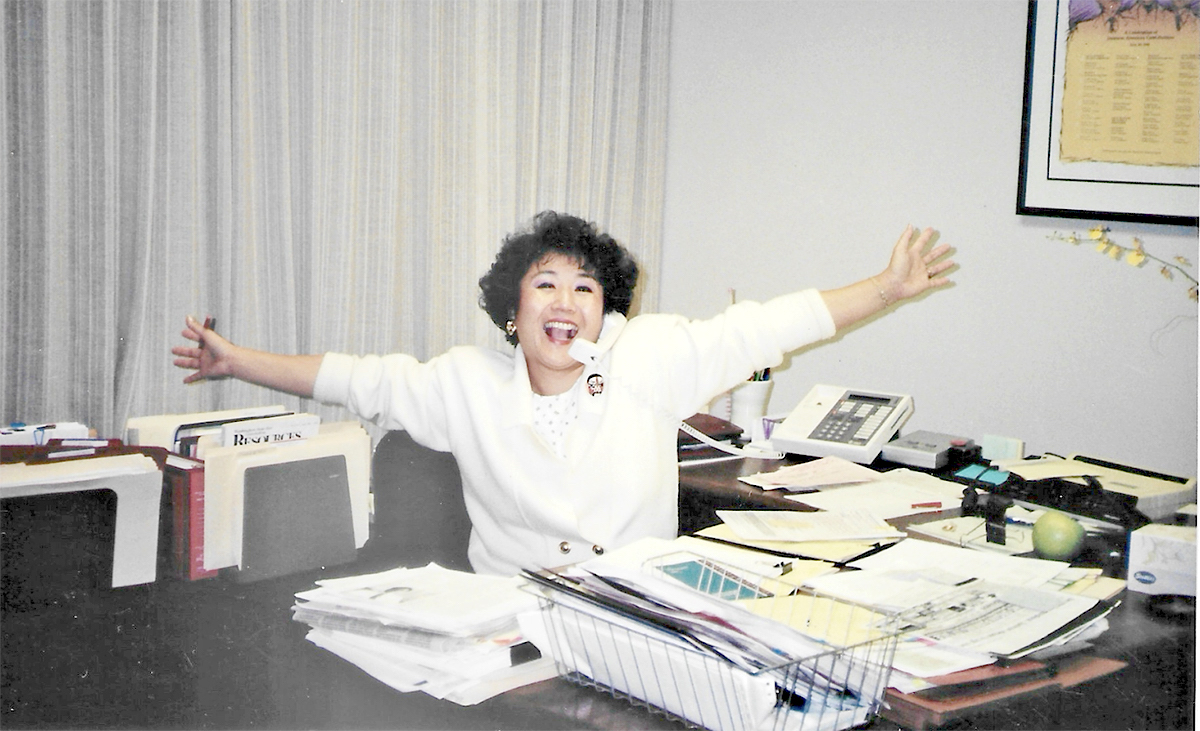

Peggy Nagae practiced law in Seattle. (Photo: Courtesy of Peggy Nagae)

On all three legal teams, women did the work on many different levels, but either felt uncomfortable to take credit or were not given the space to claim what was rightfully theirs. Almost everyone associated with the cases who were interviewed for this article talked about the greater good — that everything outside of themselves including the Japanese American community, their clients and democracy — mattered more than their work and selves.

In life, Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga echoed this sentiment, according to Lisa Abe Furutani, her daughter. Herzig-Yoshinaga worked closely with the legal teams to find evidence at the National Archives. She befriended the archivists, spent hours poring over documents and transcribed pertinent information onto index cards that crowded her dining room table and bathtub. When it came time to reflect on her legacy, Herzig-Yoshinaga mostly demurred. Friends and supporters championed her role in the coram nobis cases.

“Mom always saw herself as part of the team,” said Furutani, 73.

Being humble and a team player are, of course, valuable attributes. But do they come at the expense of being diminished? Humbleness isn’t a malignant enemy with ill intent. It’s in the air and the water of the community, said Nagae.

It’s the implicit bias that determines appropriate behavior and wordlessly seeps into the next generation.

If All Else Fails, Get a Bigger Table

In her book “Unlearning Silence,” Elaine Lin Hering says power is invisible to those who have it. If in any given space, you are the person who is most often asked to speak, she says, then use your social capital to elevate the voices that are not often heard.

In hindsight, many of the lawyers on the cases wish they could have done some things differently to ensure a more accurate telling. Be more inclusive. Defer more publicity to the other cases. Speak up instead of falling silent. Misinformation perpetuates in silence, says Hering in her book. It starts so subtly that we may not notice it.

Photos of Korematsu at press conferences surrounded by his lawyers are immortalized in books, nonprofit organizations’ websites and academic research papers. These photos play large roles in forming the historical narrative of the cases. In an often-published photo of Korematsu at a San Francisco Press Club press conference, Lorraine Bannai stands behind the table dressed in vertical stripes.

In the last few years, she has written articles elevating the women who worked on the Korematsu legal team — Kai, Leigh-Ann Miyasato and Donna Komure — as well as the women who worked on the other coram nobis cases, including her older sister, Kathryn Bannai.

Historical narratives are about past events. But they are continually being reinterpreted and rewritten. It’s never too late to set the record straight.

Kathryn Bannai with her sons, Jared (left) and Sean

In recent years, the women of the coram nobis cases have been more intentional in speaking about their roles. They’ve written about their experiences, given talks and participated in panel discussions about the impact of the cases. These opportunities give them visibility and the chance to become the role models they never had as young lawyers.

“Claim your space when there’s a table, a meeting, a room, a photo,” said Lorraine Bannai, 69, professor emerita and director emerita of the Fred T. Korematsu Center for Law and Equality at Seattle University School of Law.

And if there is pushback, suggest getting a bigger table.

“This isn’t about you,” she said, “It’s about the future.”