This second installment focuses on Mikuriya’s research successes.

By Rob Buscher, Contributor

[Editor’s note: The following article is a continuation from the May 22-June 4, 2020, issue of the Pacific Citizen about the early career of Japanese American medical marijuana pioneer Dr. Tod Mikuriya. Read part one of the story here.]

Although Dr. Tod Mikuriya’s time at the National Institute of Mental Health was brief, his experience working within a federal agency would shape his thinking for decades to come. It was clear to him that based on the overwhelming scientific bias that he witnessed at the NIMH, the government had committed to willful ignorance of the medicinal properties of cannabis.

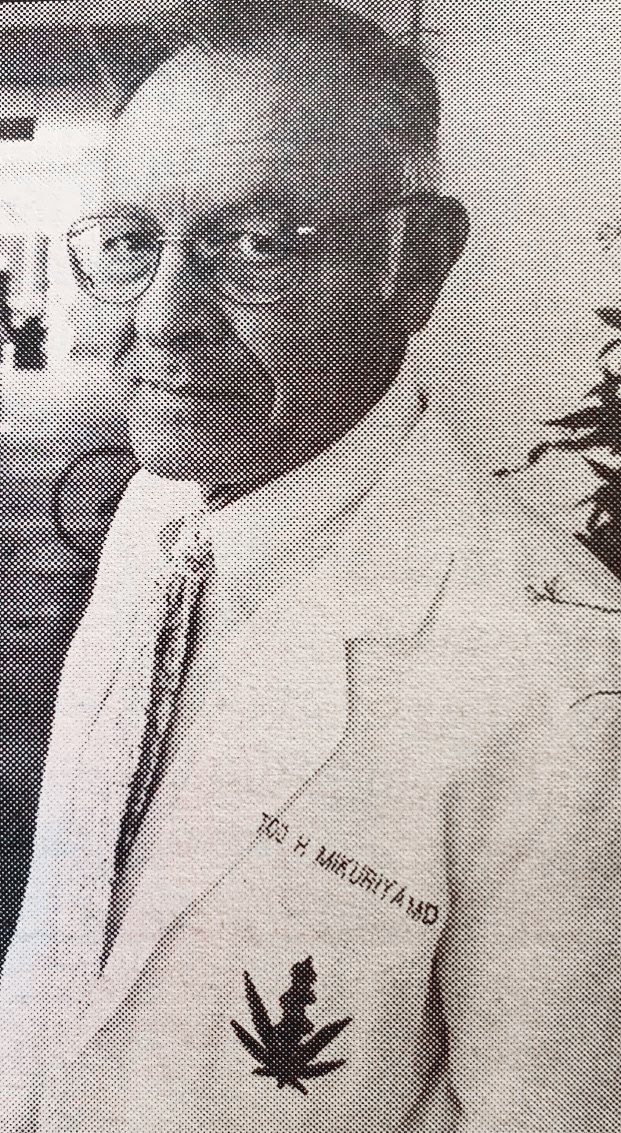

Mikuriya was featured in a 1972 California Statewide Steering Committee Proposition 19 ad for the decriminalization of marijuana. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mikuriya Family)

After compiling the data for his “Position Paper on Marihuana,” Mikuriya was convinced that the only sensible course of action was for the government to decriminalize the substance so that medical researchers could resume scientific study of its medicinal properties that were once widely acknowledged in U.S. pharmacology prior to the 1937 prohibition.

In 1970, Mikuriya moved to Berkeley, Calif., where he would become a fixture in the medical marijuana movement. In 1971, he joined Amorphia, a special interest group that was spearheading the California Marijuana Initiative.

Mikuriya consulted on the medical language used to support the ballot initiative also known as “Proposition 19” — to decriminalize the personal use of marijuana for persons 18 years of age or older — which was put to a vote in the 1972 California general election.

Fellow CMI advocate Gordon Brownell recalled, “With his short hair, sharp clothes and pleasant smile, Tod was a good spokesperson in the legislative arena. He particularly liked it when he could confront a conservative Republican legislator and go up to him and say something like, ‘Hi. I’m a medical doctor and a Republican. Do you support decriminalization of marijuana and getting the government out of our private lives?’”

Aside from his clean-cut appearance and professional credentials, what made Mikuriya stand out from other marijuana activists was his focus on the medical applications of cannabis. Although the CMI was defeated, it garnered support from more than a third of the electorate.

Fellow advocate Michael Aldrich, Ph.D., explained in the “Dr. Tod” biopic documentary, “We regarded 30 percent of the statewide vote as an enormous victory. It meant that for the first time anywhere, California proved that marijuana had an actual political constituency, particularly in San Francisco, Santa Monica and other liberal places. But it was an active political constituency. And George Moscone, who was our state senator from San Francisco at the time and our state Senate Majority Leader, understood right away that because the overwhelming third voted in favor of legalizing marijuana cultivation and possession throughout the state, the constituency deserved the opportunity to lower the penalties for marijuana at the very least.”

Dr. Tod Mikuriya when he worked at the NIMH (Photo: Courtesy of the Mikuriya Family)

With their newfound support from Sen. Moscone, Mikuriya and his fellow advocates spent the next two years convincing the Republican majority State Senate committees related to narcotics enforcement that California could save as much as $100 million a year by decriminalizing marijuana possession for personal use.

Aldrich continued, “The reason for the cost was because possession for any amount of marijuana was punished as a felony, and that meant that you had to go to state prison for at least a year if you got caught with even a seed in your purse. We worked out the figure between arrest costs, parole officers, the cost of courts and incarceration involving marijuana cases.”

One of the challenges that Mikuriya and other advocates faced was the lack of a comprehensive bibliography of the medical uses of cannabis. In 1973, Mikuriya amassed the many resources he had collected over the years into a compendium guide for medical practitioners that he titled “Marijuana Medical Papers 1839-1972,” which he self-published through a loan from his parents.

Referencing their parents’ progressive attitude toward Mikuriya’s work, Mary Jane Mikuriya wrote, “My parents’ understanding of medical marijuana evolved with Tod’s evolution and discovery of its many uses throughout history. Mother was a trained research scientist who found the information Tod was discovering over time very interesting. Their long conversations, actually more like a friendly scientific cross examination about cannabis, its side effects, its cultural uses and practices were very interesting to her. She was pleased and proud Tod was working to help his patients. She supported him speaking out to help those in need, even if it was against the law.”

Marijuana has been a highly controlled substance in Japan since 1948, where even today, getting caught with a gram or less intended for personal use can carry up to five years’ imprisonment and a hefty fine.

However, the elder Tadafumi Mikuriya also supported his son’s work.

“Dad was always supportive and proud of Tod as he spoke up and challenged social norms,” said Mary Jane Mikuriya. “He followed him carefully and shared the news of Tod’s activities, good and bad, with our Japanese relatives.”

Thus, with his parents’ blessing and financial backing, Mikuriya created the most-comprehensive volume of medical marijuana texts to date — a much-needed asset in the ongoing effort to legalize marijuana. An excerpt from the introductory statement of Tod’s publication reads:

Medicine in the Western World has forgotten almost all it once knew about therapeutic properties of marijuana, or cannabis. Analgesia, anticonvulsant action, appetite stimulation, ataraxia, antibiotic properties and low toxicity were described throughout medical literature, beginning in 1839 when O’Shaughnessy introduced cannabis into the Western pharmacopoeia. As these findings were reported throughout Western medicine, cannabis attained wide use. Cannabis therapy was described in most pharmacopoeial texts as a treatment for a variety of disease conditions.

The active constituents of cannabis appear to have remarkably low acute and chronic toxicity factors and might be quite useful in the management of many chronic disease conditions. More reasonable laws and regulations controlling psychoactive drug research are required to permit significant medical inquiry to begin so that we can fill the large gaps in our knowledge of cannabis.

Mikuriya’s book, along with another study he led titled “Costs of California Marijuana Law Enforcement,” helped win over the fiscally conservative Republican leadership in Sacramento, who would enact SB 95 in 1975. The bill decriminalized possession of marijuana for personal use under one ounce from a felony to a misdemeanor.

Mikuriya would spend the next 15 years continuing to lobby for marijuana reform, which was increasingly difficult during the return to social conservatism marked by the Reagan presidency years.

Mikuriya with his sisters, Beverly and Mary Jane, and their parents, Anna and Tadafumi (Photo: Courtesy of the Mikuriya Family)

It was not until the AIDS epidemic of the early 1990s when the pathway to legalizing medical marijuana would finally open. Lacking access to proper medical care amidst society-wide prejudice at a time when little was known about their disease, many AIDS patients had taken to self-medicating with marijuana as a solution to pain management and restoration of appetite.

Acknowledging the opportunity that this presented, pro-marijuana advocate Dennis Peron mobilized San Francisco’s gay community and its allies to successfully campaign for Proposition P — a ballot question in the city election that would lead to the legalization of medical marijuana in the city of San Francisco.

Mikuriya was asked to write the text of the ballot question, which read:

The people of the city and county of San Francisco recommend that the State of California and the California Medical Association restore Hemp medical preparations to the list of available medicines in California. Licensed physicians shall not be penalized for, or restricted from, prescribing Hemp preparations for medical purposes to any patient.

The term Hemp medical preparations means all products made from Hemp, Cannabis, or Marijuana in all forms that are designed, intended, or used for human consumption for the treatment of any disease, the relief of pain, or for any healing purpose including: the relief of asthma, glaucoma, arthritis, anorexia, migraine, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, nausea, stress, for use as an anti-biotic and anti-hematic, or as any healing agent or as an adjunct to any medical procedure for the treatment of cancer, HIV infection or any other medical procedure or herbal treatment.

Mikuriya was deliberate in his choice of words to “restore Hemp medical preparations” using this opportunity to educate the public about the past inclusion of medical cannabis in the U.S. pharmacopeia.

Prop P passed by an overwhelming margin of 4-to-1, paving the way for the first medical marijuana dispensary, the San Francisco Cannabis Buyers Club, to open. Mikuriya helped draft the intake protocol for the dispensary, which included a required letter of diagnosis from a licensed physician. In the years that followed, he would continue his advocacy efforts for statewide legislation that would eventually be introduced in 1996 as Proposition 215.

Mikuriya explained in his biopic documentary, “As one of the authors of the Prop 215, my claim to fame is getting the phrase ‘for any other condition that Cannabis is helpful’ included.”

He would also write the protocols for dozens of other dispensaries that were opened after Prop 215 passed. In the aftermath of the statewide legalization of medical marijuana, oncologists and AIDS specialists largely embraced cannabis as part of their treatment plans, but few others were willing to do so.

Decades of information suppression regarding the medical uses of cannabis meant that physicians knew little about its effects, appropriate dosage or even what conditions it could be used to treat.

Additionally, because federal law still forbade the use of marijuana as a controlled substance, law enforcement agencies threatened to revoke prescription-writing privileges of doctors who approved marijuana use.

Despite the legislative victories in California, the Clinton administration had elevated the Office of National Drug Control Policy to a cabinet level department, and by the end of 1996, over 544,700 individual arrests were made on marijuana possession charges nationwide.

Mikuriya’s high-profile role in the medical marijuana movement drew the ire of Barry McCaffrey, the director of ONDCP, colloquially known as the “Drug Czar” who publicly ridiculed Mikuriya’s medical philosophy as “a Cheech and Chong Show.” Even today, the debate about whether state laws on marijuana can supersede federal laws is a legal grey area that patients and medical practitioners must navigate with caution.

Not knowing how long he would be able to operate under the precarious legal circumstances, Mikuriya felt a sense of urgency to authorize as many patients as possible and thus opened the Mikuriya Practice in 1996, where he began practicing cannabis therapy full time.

Never losing sight of his Japanese heritage, Mikuriya used the family mon crest on his business cards and website. As a psychiatrist, his examination mainly consisted of a discussion about the patient’s history related to mental and emotional health and did not include a physical.

Unfortunately, this would be his undoing as state and federal law enforcement conspired with the conservative-leaning members of the Medical Board of California, who strongly opposed Prop 215 to fabricate a formal investigation into his practice in 2003.

Mikuriya’s attorney, Bill Simpich, explained, “The hardcore anti-215 crowd in the attorney general’s office realized they were going to lose and decided to round up all the reports filed by district attorneys and cops who were ‘sore losers’ in Prop 215 cases and seek the records of the victorious patients.”

The case deviated from the normal protocols related to medical board investigations, which are typically only conducted when patients or health-care providers issue a formal complaint. Documentation from state medical board records support this claim, as the record shows all complainants were members of law enforcement.

In an article from the fall 2015 issue of Nevada County Cannabis, patient advocate Bobby Eisenberg wrote, “The case against Dr. Tod was nothing short of a good old-fashioned witch-hunt. Not one patient filed a complaint against Tod, nor was there any evidence that a single patient had been harmed. The District Attorneys and Sheriffs were frustrated being unable to successfully prosecute legitimate cannabis patients for possession and cultivation due to Tod’s recommendations and testimonies.”

During the trial proceedings, Mikuriya once again found solace amidst the Quaker community from the Quaker Fellowship he belonged to in Berkeley. Several of his Quaker friends attended the trial as a show of solidarity.

Beverly Mikuriya wrote, “These white men, well-connected, dressed in business suits, sat facing the judge and stood out from the rest of the attendees at the trial because they all wore a 4-inch-wide round lapel button that said, ‘Witness.’ They came in each session and did not talk among themselves nor to anyone at the trial, but their presence was very noticeable. Tod was comforted by their support — once again, the Quakers played an important role during Tod’s life.”

In January 2004, the Medical Board of California ruled that Mikuriya had committed gross negligence and nearly revoked his license. An excerpt from the ruling alleges that Mikuriya “committed acts of gross negligence, repeated negligence, recommended and approved the use of a controlled substance without conducting a prior good faith examination and failed to maintain adequate and accurate medical records in the care and treatment of 16 patients.”

Mikuriya’s penalty was reduced to a hefty fine and probation period of five years, but it left a lasting impact on his outlook for the remainder of his life.

Mary Jane Mikuriya wrote, “What Tod went through with medical cannabis was just like living again during the war years … waiting for the next personal attack, and he never knew where it might be coming from.”

Dr. Tod Mikuriya

Mikuriya shared similar sentiments in one of his final interviews with O’Shaughnessy’s journal that was published posthumously: “The cannabis prohibition has the same dynamics as the bigotry and racism my family and I experienced starting on Dec. 7, 1941, when we were transformed from normal-but-different people into war-criminal surrogates.”

After being diagnosed with cancer in March 2006, Mikuriya continued to see patients and had an active role in organizing a medical marijuana symposium in March 2007 before succumbing to his illness in May 2007.

Mary Jane Mikuriya recalled her brother’s funeral service, where more than 300 attended.

“In the Quaker tradition, each participant stood up to tell some remembrance of the deceased. The remembrance event took over three hours, and people just did not leave the memorial. At the reception, people told one another how Tod spoke up against the law on their behalf,” she remembered.

Mikuriya was buried in the Quaker cemetery across from his childhood home in Fallsington, Pa.

Although he did not live to see his vision fully realized, so many of the medical marijuana movement’s victories in the past decade can be directly attributed to the work that Mikuriya began.

Medical marijuana has been legalized in 33 states, including the District of Columbia. All but six of the Democratic presidential primary candidates were in favor of outright legalizing marijuana. Presidential candidate Joe Biden wants to let the states decide and is in favor of scrapping past federal marijuana convictions.

Longtime JACL sponsor AARP issued a statement from its board of directors in September 2019, with the organization “supporting the use of medical marijuana in the states that have legalized it and supporting further research on medical use of cannabinoids to help alleviate the symptoms of diseases and the side effects of the treatment for diseases.”

Perhaps it is time that the JACL consider an official policy position on the subject as well. Civil rights group ACLU has actively opposed marijuana prohibition since 1968, objecting to the government’s criminalization on the grounds that it violates “the rights of individuals to make choices concerning their own bodies and private behavior.”

The ACLU further explains in its statement, “Marijuana prohibition and the policies surrounding it result in a series of other civil liberties violations, including threatened rights to free speech and protection from illegal searches and seizure.” Between 2001-10, more than 7 million arrests were made for marijuana possession alone. Data gathered by the ACLU shows that the policing and enforcement of marijuana laws are also significantly biased along racial lines. Although more white Americans use marijuana on a regular basis, African Americans are actually 3.73 times more likely to be arrested. Selective prosecution of these cases has likewise resulted in a disproportionate number of African Americans serving jail time on low-level possession charges.

Regardless of whether the JACL adopts a formal stance on this issue, it is clear that the Japanese American community has long held stake in this conversation, thanks to the tireless advocacy of Dr. Tod Mikuriya.

Special thanks to Mary Jane and Beverly Mikuriya for sharing their memories and photographs that helped shape this article and Fred Gardner for the wealth of information about Dr. Tod Mikuriya and the medical marijuana movement published in his O’Shaughnessy’s journal.