The long-lost stone monument to James Hatsuaki Wakasa was excavated on July 27, 2021. (Photo: Nancy Ukai.)

Pilgrims gather in Delta, Utah, to mark the 80th memorial of the slain incarceree and honor all who died in the WWII American concentration camps.

By Nancy Ukai, Contributor

Eighty years after James Hatsuaki Wakasa was murdered by a guard at the Topaz, Utah, concentration camp, Japanese Americans from ages 9-92 came from across the country to pay their respects and retrace Wakasa’s last steps before he was shot in the chest and killed on April 11, 1943.

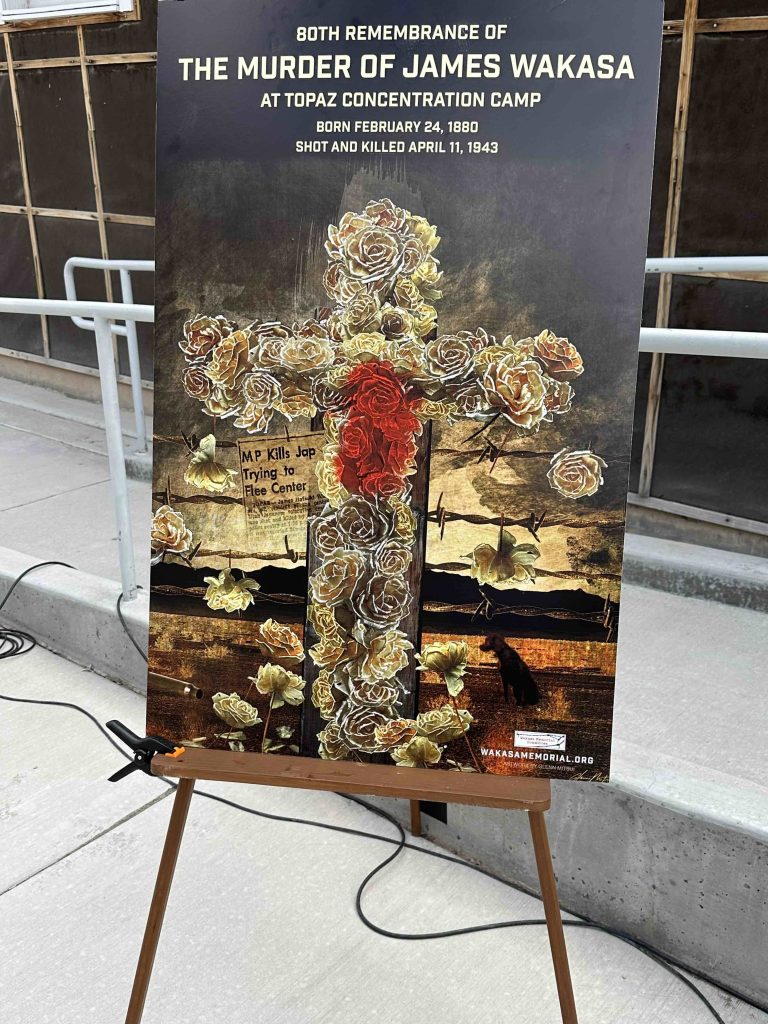

Poster by Topaz descendant Glenn Mitsui (Photo: Nancy Ukai)

On a dry, sunny morning last month, a group of approximately 120 walked a quarter of a mile in silence from Wakasa’s barrack at Block 36-7-D to the exact place where he died, inside the camp’s barbed-wire fence. Another group of 15 sat in folding chairs outside of the fence.

“It was powerful to do the walk and try to imagine what it was like to be there,” said Lisa Doi, president of the JACL’s Chicago chapter.

“As a Yonsei, I try to imagine what it was like for my great-grandparents who were incarcerated,” she said.

Eric Pikyavit, a member of the Kanosh Council, blessed the land and asked people “to forgive but never forget.”

He told the group that “walking over, I could feel a lot of energy, and as I got closer (to the fence), it was turning to a lot of pain.”

The participants attended memorial events on April 21-22 that were co-hosted by the Wakasa Memorial Committee, which first proposed the idea, and the Topaz Museum Board.

The weekend’s commemoration followed an earlier tribute to Wakasa that was held in San Francisco’s Japantown Peace Plaza on April 11 (see Pacific Citizen’s April 21-May 4, 2023, issue. See related story in Pacific Citizen’s Oct. 8-21, 2021, issue.)

The Wakasa Memorial Committee created the ceremonies, while the Topaz Board managed the logistics and organized an evening at the Salt Lake Buddhist Temple. Paper flowers were folded, and presentations were made on Wakasa’s life by this writer and archaeology at Topaz by Utah State Historical Preservation Office archaeologist Chris Merritt and on the Wakasa memorial by stone expert John Lambert.

Pilgrims traveled from California, Illinois, Indiana, New York, Oregon, Salt Lake City, Washington and Washington, D.C., to “pay attention,” said Rev. Duncan Ryuken Williams, a Buddhist priest, because “attention is love.”

Chizu Omori, 92, a Poston survivor, holds a flower made in Wakasa’s hometown of Ishikawa Prefecture. (Photo: Nancy Ukai)

“To love someone even if we have never met them is to pay attention. None of us gathered here today ever met James Hatsuaki Wakasa,” Williams said. “He left no family, no descendants to remember him, so it is up to us to remember him.”

An important part of the morning ceremony was to purify and bless what writer and Topaz Stories Editor Ruth Sasaki called the “cursed land.”

“When Mr. Wakasa was shot, his blood became a part of this land,” Williams said.

Rev. Amy Uzunoe of the Konko Church of Portland, Ore., threw salt over the site where Wakasa died and into the indentation in the land where his monument had been removed 20 months earlier by the Topaz Museum Board, which engaged the services of a local forklift operator.

This pre-emptive action gave rise to the formation of the Wakasa Committee, which advocates for professional protection of the site and equal partnership with community members in decisions on the site and artifacts.

But defenders of the Topaz Museum say that an apology has been made, and that all must “move on.”

A positive step toward reconciliation is the cooperative meetings currently being convened by the Utah SHPO, which brought together three members each from the board, the committee and state and federal officials, plus a stone expert. The meetings began in September 2022.

The place where Wakasa was killed was a source of contention in 1943, too, Rev. Yoshii noted.

Topaz incarcerees wanted to hold Wakasa’s funeral in 1943 at his death spot but were “vetoed,” he said in his sermon.

“The administration was concerned that if they allowed the funeral to be held at the site of his death, people would be stirred to unrest and perhaps massive protest. This was the ultimate in crowd control and silencing of people’s voices,” Yoshii said.

Attendees lined up to offer paper flowers at altars set up on both sides of the fence.

Like the funeral of 2,000 mourners in 1943, paper flowers were in abundance. But this time, flowers were made by schoolchildren in Wakasa’s hometown in Ishikawa Prefecture, carried from Japan to Utah by this author and also by 21st century friends of Wakasa: historians in Georgia, children in Portland and Seattle and a 97-year-old Nisei in San Francisco whose husband was incarcerated at Topaz.

Rev. France Davis (left) and Rev. Michael Yoshii tie paper flowers to the barbed-wire fence. (Photo: Nancy Ukai)

Civil rights leader Rev. France Davis, retired minister of the Calvary Baptist Church in Salt Lake City, walked with former Utah State Sen. Jani Iwamoto to the site where he read scripture. Rev. Davis marched with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1965 from Selma to Montgomery for voting rights.

Joshua Shimizu beautifully sang “Rock of Ages” in the desert, ending with a verse in Japanese, as it was sung in 1943.

An afternoon ceremony at the Topaz Museum was led by Williams and Uzunoe to purify the Wakasa stone monument.

After the ceremony, survivors and descendants were invited to line up and touch the stone to reconnect with the hands of their Issei ancestors, who would have been the last people to touch it before the boulder was pushed into the ground and buried. It rested in the earth for 77 years.

Among the event’s attendees was a three-generation family who drove from Vacaville, Calif., to attend the ceremonies. The youngest, 9-year-old Akimi, saw her great-great-grandfather’s name on a Topaz quilt of obituaries researched and designed by Topaz descendant Kimiko Marr. It hung in the Delta community center where the stone ceremony was live-streamed.

“Nanny, we found grandfather’s name!” Akimi told her obaachan, Sharon Mayeda Godfrey. The family of four touched the Wakasa stone and pledged to learn more.

Nancy Ukai is a director on the Berkeley JACL board and a member of the Wakasa Memorial Committee.

Pictured (from left) are JACL members David Inoue, Lisa Doi, Karen Kiyo Lowhurst, Barbara Takei, Nancy Ukai, Satsuki Ina, Stan Hirai, Kenzie Hirai, Mari Nakamura, Alex Hirai and Jani Iwamoto. (Photo: Mike Ishii)