This contemporary image of the F.M. Hall building at 2700 Larimer Street in Denver shows the former site of the T.K. Pharmacy, operated by Thomas “Tommy” Kobayashi and Tak Terasaki. When the building was renovated in 2012, a cache of hundreds of WWII-era letters written by incarerees from different WRA Centers to the pharmacy were discovered. (Photo: Dean K. Terasaki)

When family history is deliberately left untold, those left behind must process the blank spaces.

By Lynda Lin Grigsby, Contributor

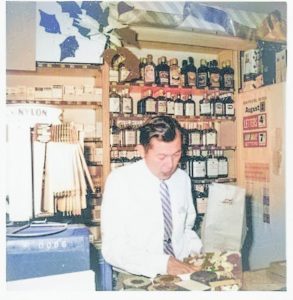

Tak Terasaki’s memory was always sharp. Mention a golfer, and he could rattle off an average score or recite the corrupt players ensnared in the 1920s Teapot Dome scandal. It was as if he had a limitless repository of information that he delighted in relaying to family members.

“He was a historian who always told us everything,” said Melanie Froelich Terasaki, Tak’s youngest daughter.

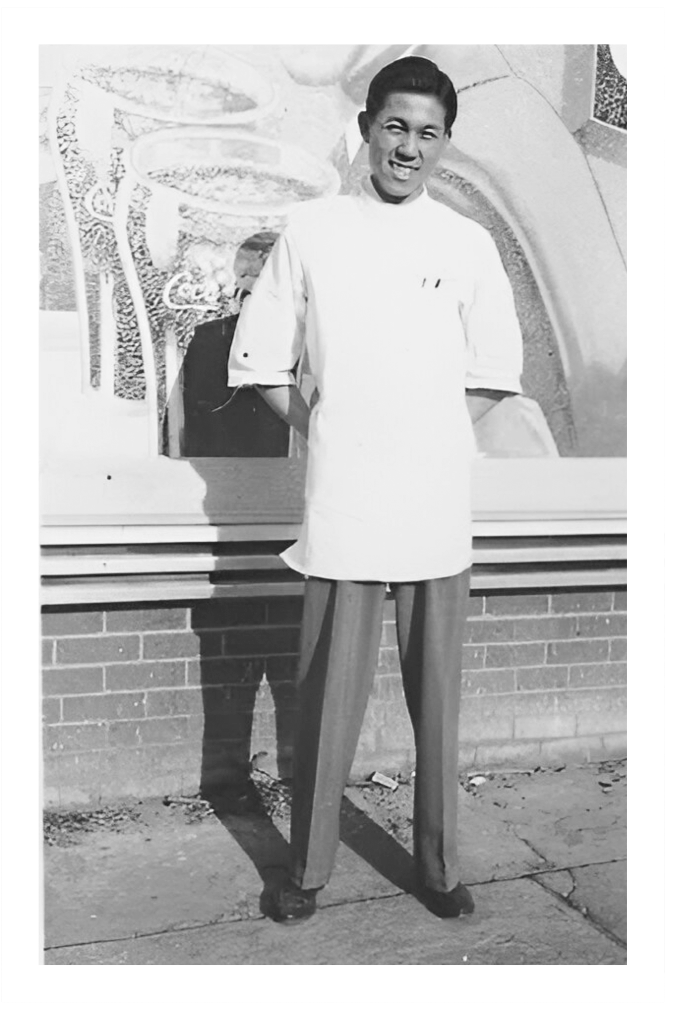

“He was a superhandsome man,” says Kiku Terasaki about her father, Tak Terasaki. “He was six feet tall, one of the tallest Japanese guys in town.”

But deep in the recesses of Tak’s memory, he kept a secret. The longtime pharmacist and shrewd businessperson ran one of the few Japanese American working pharmacies in the West during World War II. From 1938-65, Tak worked alongside family members at T.K. Pharmacy, a standalone brick building at the corner of 27th and Larimer Streets in Denver. When he died in 2004 at 89, no one knew about the hidden treasure until long after T.K. Pharmacy closed its doors forever.

In 2012, the vacant brick building at 2700 Larimer Street was undergoing renovations. Hundreds of WWII-era letters from Amache to Heart Mountain and beyond were inside a wall. Some were formally addressed to “Dear Sir” or “Gentlemen.” Others were more personal:

“Dear Tak,” wrote someone on Dec. 20, 1943. “Is it cold there?”

The discovery of the letters set off an initial wave of intrigue. Since the discovery, the correspondences have been preserved in a digital repository of elegantly handwritten letters on sepia stationary — free for anyone with an internet connection to peruse. From the boxes, 557 objects have been digitized as a part of Densho’s T.K. Pharmacy collection (https://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-319/). But more than a decade later, many questions remain. Why were these letters put in the wall? And most puzzling of all, why didn’t Tak say anything about them?

“To not say anything about this is major,” said Melanie, 72, a Sansei from Evanston, Ill. “It’s a mystery.”

People Speaking in the Letters

Before its 2012 renovation, the building was a ghost of its former glory. For seven years, it stood empty. In its last identity as a deli before the facelift, the building saw its doors and windows barricaded with iron security bars. Inside, filtered sunlight danced off the raised patterns of the tin ceiling tile. In the dilapidated walls lived a unique collection of letters that showed the humanity of the average person in camp.

“It’s people in camp writing to an actual Japanese American-owned pharmacy requesting things,” said Caitlin Oiye Coon, archives director at Densho. “They could have ordered the same things from Sears, but it was a deliberate decision to order from T.K.”

T.K Pharmacy had a soda jerk and served famous chili. The Narahara sisters are pictured outside of T.K. Pictured (from left) are Shizuko, Fujiko and Emiko, or more commonly known as Pat, Fudge and Em, respectively. (Photo: Courtesy of David Fujioka)

In those days, neighborhood pharmacies functioned as places of convenience — a one-stop shop for medicine, soap and maybe even a comic book or a model airplane kit. T.K. Pharmacy was one of those classic spots with a soda jerk counter, jukeboxes and a kitchen in case one needed a bowl of chili, too.

Tak Terasaki co-founded the Mile High JACL. (Photo: Courtesy of Melanie Terasaki)

Denver was outside the military exclusion zone during WWII, so the Japanese American-owned-and-operated pharmacy continued to serve its neighborhood. For Japanese Americans during this time, the camp version of a drugstore run was to write to T.K. Pharmacy.

From Tule Lake in 1943 came a request for a bottle of “Kola-Black” hair dye, a popular demand. Someone in Santa Fe, N.M., requested hay fever medication. Many were orders for sake and everyday supplies like notebooks and film.

The letters represent a snapshot of life under extraordinary circumstances. Sometimes, the requests were for a semblance of normalcy, like sake to commemorate a birthday or wedding. Other times, they were reminders of the cruelty of the human condition during wartime.

Some letters are so personal that Densho redacted names, especially if the correspondences had medical-related information. In a June 6, 1943, letter from Amache, someone wrote to T.K. Pharmacy asking what medication could induce an abortion.

“You can hear people speaking in the letters,” said Megan Undeberg, a clinical pharmacist and associate professor of pharmacotherapy at Washington State University, who studied the collection while it was being digitized at Densho. It’s a passion project, Underberg said in a video interview, that grew from her interest in WWII history. She researched and interviewed people associated with T.K. Pharmacy. What’s a five-hour drive to Densho headquarters in Seattle, said Undeberg with a lilting laugh, if that meant she could hold the letters?

The letters chart the different phases of the forced evacuation and incarceration, including the first months when the infrastructure wasn’t in place yet to accommodate the volume of families. One letter tersely asked for medical treatment for their children’s pinworm infections. To a pharmacist like Undeberg, this makes sense. Assembly center and camp conditions were notoriously inhospitable, and sanitation was poor.

“It’s not their fault,” said Undeberg. “They’re not dirty or unclean or unkempt, but the facilities themselves are this way. Where were the health facilities within the camps?”

The Terasaki Family in an undated photo. Pictured (from left) are Masayemon, Miko, Shoziro “Saaj,” Sei, Yutaka “Tak,” Yuriko and Saburo “Sam” (front). Haruko, the oldest daughter who was married to Thomas Kobayashi, is not pictured. (Photo: Courtesy of Melanie Terasaki)

Consider this: What may it have felt like to write to a pharmacist in Denver to get deworming medication for ailing children? Undeberg pauses under the weight of this thought.

“They had nothing.”

Desperation Between the Lines

Most letters have exquisite penmanship and the politeness of a bygone era. Because they were mainly Issei writing, many of the letters were written in Japanese. Naoko Tanabe is helping Densho translate the letters written in Japanese. To date, 60 of the correspondences have been translated to English.

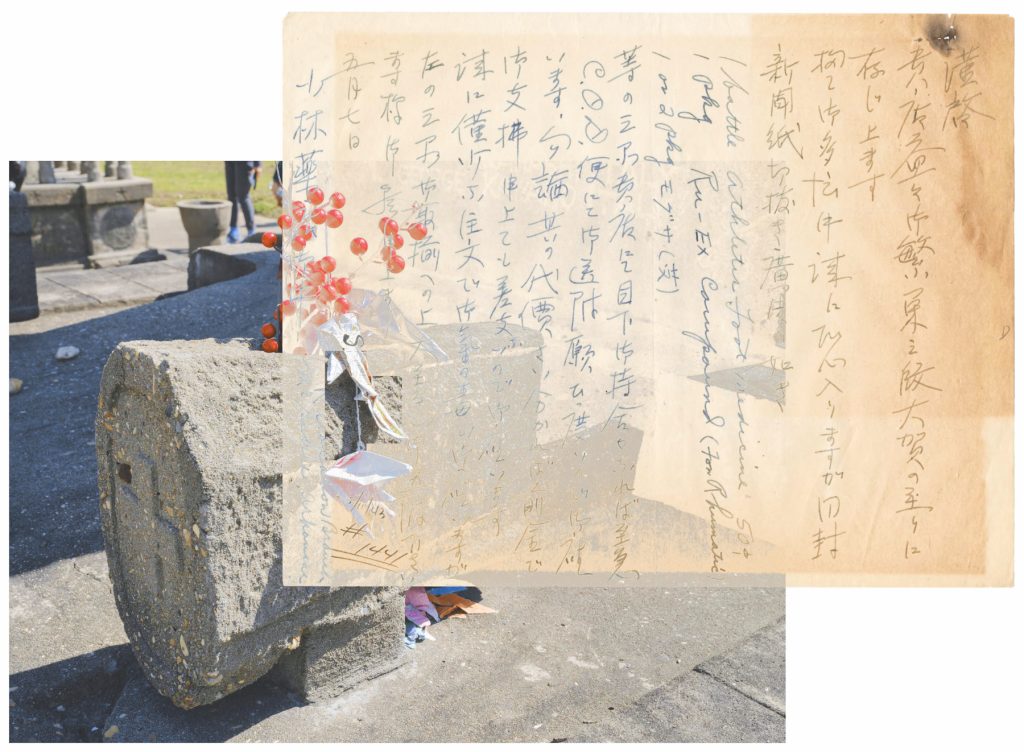

A photomontage created by Dean K. Terasaki from two images. The photograph is a detail of the monument for the 100th/442d/M.I.S. at the Rohwer Concentration Camp near McGehee, Arkansas, taken in 2023. The other is a 1943 letter requesting for Athlete’s Foot medication and Ru-Ex Compound for rheumatic arthritis. / Letter courtesy of the T.K. Pharmacy Collection, Densho. Artwork is a Creative Commons: BY NC SA.

“You can kind of feel this kind of desperation,” said Tanabe. “It’s a little depressing to translate those letters one after another.”

The wording of the letters is often straightforward: Please send supplies. But the subtext of desperation lies in the politeness and the almost wistful mentions of upcoming holidays.

“You can tell that none of these things are available for them,” said Tanabe.

An April 19, 1943, letter from California urged T.K. Pharmacy employees to “please don’t send back my check. Send me anything.”

Businessman or Hero?

T.K. Pharmacy’s slogan was a no-frills decree of what the company offered: “cut-rate drugs, liquor, prescriptions.”

After the discovery, the widely accepted narrative described how a Japanese American pharmacist provided much-needed assistance to the community of incarcerated Japanese Americans. To advertise its services to the incarcerated Japanese Americans, T.K. Pharmacy placed advertisements in Japanese American newspapers like the Colorado Times and Rocky Shimpo, said Coon.

In a March 17, 1943, letter to a hair dye manufacturing company, Tak wrote that because T.K. Pharmacy was “one of the few if not the only store left in the country operated by Japanese Americans,” it was getting “flooded” with requests.

“He was still a very shrewd businessman,” said Undeberg. “He didn’t give the stuff away for free.”

An alternate narrative emerged, painting T.K. Pharmacy as using direct advertisement to target a vulnerable population.

“I don’t get that sense,” said Undeberg. “I really don’t.”

Along with pharmaceuticals and liquor, T.K. Pharmacy provided incarcerees with radios, chewing gum, lipstick, face powder and allergy tablets. These sundry items didn’t make a substantial medical impact, but likely positively affected emotional and psychological health. When the world turned away, someone outside the evacuation zone cared enough to send comfort items.

“He was a lifeline,” said Undeberg about Tak.

Mystery in the Wall

Somebody hid the letters in the wall like a time capsule. It’s like someone knew the collection would be worth talking about someday. Except Tak never spoke of the letters or the services T.K. Pharmacy offered to the Japanese American community during WWII, not during or even after redress. No one talked about what was hidden.

The front door of the F.M. Hall building, former home of T.K. Pharmacy (Photo: Dean K. Terasaki)

The absence of all primary sources makes solving a mystery like this challenging. When family history is deliberately left untold, those left behind must process the blank spaces.

“I don’t think that it was like an intentional ‘I’m going to hide these records in the wall’ situation,” said Coon. As an archivist, she’s heard of people who have stuffed everyday objects in walls for insulation — a pragmatic solution that can become romanticized later when the items are discovered.

“Everybody wants it to be super cool like, ‘Oh, they’re going to get raided, so they hid these in there,’” said Coon. “But I don’t think that is the case.”

The silence may be because it wasn’t a big deal.

“I don’t think that he was concealing anything,” said Kiku Terasaki, Tak’s oldest daughter. “I think that it simply didn’t come up. I think that they simply moved on with their lives.”

If Tak were still with us, said Kiku, 76, of Southern California, he would have had a lot to say. He would say the letters represented a sad commentary on the role he had to play during WWII.

“But that he was glad to do it,” Kiku affirmed.

Family Business

Yutaka “Tak” Terasaki was a striking-looking young Nisei with a shock of black hair. He stood six feet tall, an attribute he said in a 2001 interview he credits to the consumption of cod liver oil. Among the six Terasaki siblings, Tak was the oldest boy. Four of the siblings became pharmacists.

Before WWII, Larimer Street bustled with life.

T.K. Pharmacy was a family business. Some of the Terasaki men are pictured here outside the building in 1944. Shown (from left) are Shoziro ‘Saaj,’ father Masayemon and Tak. (Photo: Courtesy of Melanie Terasaki)

“That was the heart of a lot of activity, the crossroads going to north Denver,” said Tak in a transcript of a Nov. 10, 2001, interview with the Oral History Program at California State University, Fullerton.

In 1937, Tak’s brother-in-law, Thomas “Tommy” Kobayashi, started T.K. Pharmacy and helped Tak to earn his pharmacist license. Tak managed the store while Tommy, married to Tak’s older sister, Haruko, ran his medical practice upstairs in the brick building at 2700 Larimer St.

Tak describes a close relationship between him and Tommy in the interview with Art Hansen. Tak and Tommy played baseball together and worked in the same building alongside other Terasaki siblings.

Tommy grew up poor, according to family stories. He also faced his fair share of racism in the Mile High City. After the Pearl Harbor attack, a drunken assailant threatened Tommy outside the pharmacy with a shotgun, said Grant Kobayashi Hinds, his grandson. No one was physically hurt, but the psychological scars ran deep.

Tommy was an expert bridge player and an active member of the local Methodist church. He was also the community’s family doctor, so strangers would often exclaim that Dr. Kobayashi delivered babies in their families.

For a long while, T.K. Pharmacy was a business that united family members under one roof. But the bonds that got them through the extraordinary circumstances of WWII began to weaken over time. There was an understanding that Tak would put Tommy through medical school, and then Tommy would help Tak get his own store, said Melanie. The plan didn’t work out.

Tak left T.K. Pharmacy in 1965 to start his series of independent pharmacies. He also co-founded the Mile High JACL with Min Yasui.

When the letters were found in 2012, the phone rang in the home of the only living Terasaki in Colorado.

Sam Terasaki, Tak’s youngest sibling, picked up the phone.

Return to 2700 Larimer St.

Sam had a wicked sense of humor. He liked to tell the story of meeting his wife, Sara, at 2700 Larimer Street, where she worked in Dr. Kobayashi’s office as a nurse. While restocking the shelves, Sam cut his hand. He didn’t fret. He walked upstairs to get a tetanus shot from Dr. Kobayashi. Sara walked in when Sam had his pants around his ankles to get the shot. She liked what she saw, he often joked.

This story was told again at Sam’s funeral in 2019 and printed in his obituary. He was 94.

Sam, a 100th Battalion veteran and a pharmacist himself, did not know about the letters, said Dean Terasaki, his son, an artist who lives in Phoenix. After WWII, Sam and Sara moved away from the Japanese American community, so Dean’s connection with this part of his family history flickers. That sense of isolation and disconnect bleeds into his art — layers of images melt into each other and break time and space barriers. He blends images of the letters with camp historical markers in a series of photomontages.

Tak’s favorite part of the job was interacting with customers, family members say. (Photo: Courtesy of Melanie Terasaki)

In March, Dean, 69, returned to 2700 Larimer Street. It is now an upscale apparel boutique with a mood board filled with vintage images of all-American beachgoers. The bricks and bones of the building are the same.

“It was just nice to be in that space,” said Dean.

T.K. Pharmacy was the place of his genesis, where his parents met and later where he ran up and down the aisles while his family worked to supply the local community with basic needs. He remembers the shelves of familiar and foreign merchandise — trinkets, toys and all the fun things that become a core memory in a young mind.

“When the letters were found, I suddenly realized that this story is really complicated,” said Dean. All the Nisei Terasaki and Kobayashi family members who lived through WWII and may have known about the letters are now gone. No one knows why they were put in the wall.

And before all hope is lost, Tak leaves a kernel of information in the 2001 interview transcript.

Tak told Hansen, the interviewer, that after the war, he suggested that T.K. Pharmacy get remodeled to include a restaurant — what would become the soda jerk counter and booths.

Walls may have been torn down at that point, and the time capsule hidden to await the day when the voices in the letter can be heard.

Help Solve the Mystery

We need to crowdsource to solve a mystery of this caliber. Do you have any information on the T.K. Pharmacy letters? Did you or someone you know work at the pharmacy or send orders to the pharmacy? Please email information to llgrigsby@gmail.com.