Susan Kamei’s book relays the journey of mainland Japanese Americans.

By George Toshio Johnston, P.C. Senior Editor, Digital & Social Media

For attorney, educator and author Susan H. Kamei, Sept. 7, 2021, is a date that will live in celebration.

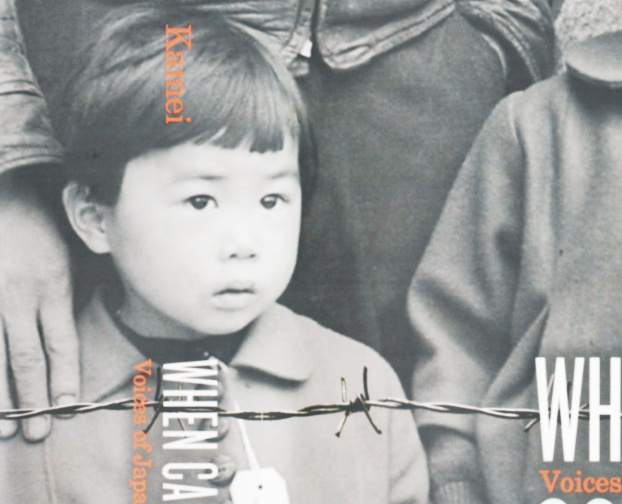

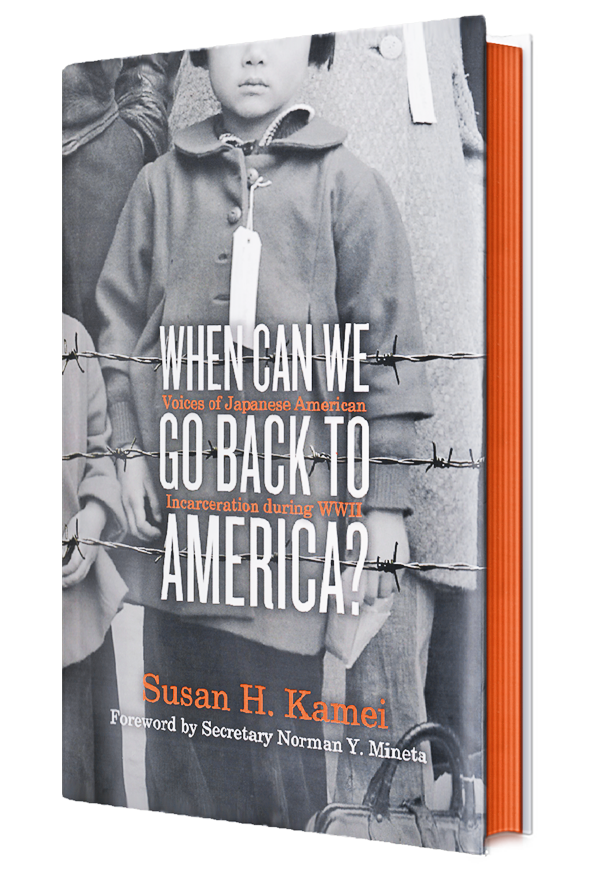

That’s when her 736-page, nearly two-pound book titled “When Can We Go Back to America?” — ISBN-13: 978-1481401449, SRP$22.99 — was officially released. “I’m getting a fair amount of ribbing over how heavy it is,” Kamei laughed.

But levity aside, the subject matter is heavy in another way, since it’s about a serious topic: what it means to be an American citizen whose race, religion or ethnicity is deemed “different” or “un-American” during a time of crisis or emergency.

“When Can We Go Back to America?” was published on Sept. 7, 2021. (Click image to order a copy of the book.)

Kamei’s “When Can We Go Back to America?” is a comprehensive narrative and reference work covering the decades-long journey that Japanese Americans began quite inadvertently after Imperial Japan attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor in the territory of Hawaii on Dec. 7, 1941.

Its forward is written by Norman Mineta, the éminence grise whose public service career includes stints as a White House cabinet member, a U.S. congressman and mayor of a major American city.

The book’s title comes from a story, possibly apocryphal, of a child who was incarcerated with her family and under the mistaken impression that they had traveled not to a government-run detention camp but to Japan, possibly because of all the other Japanese people present. The distraught child wondered aloud: “When can we go back to America?”

The first half of the massive tome is organized into Parts One through Five — what Kamei calls “the narrative” — each of which is subdivided into chapters.

As the saga unfolds, the progression of events that begin with Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor is told chronologically but supplemented with italicized memories and perspectives of people who experienced what is described.

The book’s back half follows up with biographical backgrounds of those people quoted in the narrative, along with appendices, a glossary, a timeline, index, etc.

But potential readers should not be scared off by the book’s length or fears of having to slog through an academic treatise, since those personal accounts help to humanize the history.

“It was meant to be personal, to be accessible not just to students but to the general readership,” Kamei said, alluding to how the book is under the Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers imprint.

In storytelling terms, then, “When Can We Go Back to America?” is almost cinematic, thanks to the details provided by the personal recollections. “That was the purpose of the ‘voices,’ the first-person quotes that are threaded throughout the narrative,” Kamei said.

For the Orange County, Calif.-raised Kamei, writing “When Can We Go Back to America?” was an almost natural progression for someone whose professional background includes using her Georgetown University law degree to serve as the JACL’s national deputy legal counsel and as a member of the JACL’s legislative strategy team during the redress campaign, not to mention teaching a course she designed titled “War, Race and the Constitution” at the University of Southern California.

“When Can We Go Back to America?” author Kamei is the managing director of the Spatial Sciences Institute at USC’s Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. She also teaches a course titled “War, Race and the Constitution” at USC.

Kamei points out that the course is not connected to her “full-time day job,” also at USC: serving as managing director of the Spatial Sciences Institute at USC’s Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

Although the course and book’s focus is on the mainland Japanese American experience during WWII, Kamei believes it’s part of a larger scenario that can arise when fear can pressure elected leaders, bureaucrats and fellow citizens alike to ignore the constitutional protections and civil rights of fellow Americans deemed “different” and look to politically expedient “solutions” in the name of national security or military necessity.

Kamei’s book came about after a Los Angeles Times article that coincided with the 2018 Day of Remembrance. Written by education reporter Teresa Watanabe, the article focused mostly on Kamei’s USC history course. Referenced in her article was USC history professor Lon Kurashige, who said that Kamei “was particularly well-suited to teach it” because of her role within the JACL and its contribution to the redress movement.

Watanabe’s article on Kamei and her USC course was the inciting incident that led Simon & Schuster to reach out to Kamei with an idea for a book that could tell the big picture story with a human element in a way in which a diverse readership could relate.

“Because of my background, I had the opportunity to create and teach this one course,” Kamei told the Pacific Citizen. “Anything I did for the research for the class and then ultimately for the book was just a late nights, early mornings and weekends kind of endeavor. I’m an atypical writer in that regard.”

Her background also includes being the daughter of Tami and Hiroshi Kamei, both of whom experienced the disruption of incarceration as young people, with Tami having been incarcerated at the Heart Mountain WRA Center in Wyoming and Hiroshi at Arizona’s Poston. (See sidebar.)

Although the book came together relatively quickly — she officially began in June 2019 — much of the effort, in addition to the writing, came in the form of tracking secondary source materials to their original sources or first references.

“Over time there was this game of ‘historical telephone’ that would go on, so somebody would quote somebody who would quote somebody who would quote somebody, and then I’d trace it back to either somebody’s original research, in which I’d just have to trust them or to a primary document, a newspaper article or a statement from one of the commission hearings,” Kamei said, referring to the public hearings conducted by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in the early 1980s.

Author Susan Kamei displays her new book, “When Can We Go Back to America?” (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

As for how much of her book involves JACL and its role in the redress movement, Kamei said “quite a bit,” from the origins of the organization before it became “the JACL” from the perspective of Misao “Sadie” Marietta (Nishitani), widow of James “Jimmy” Sakamoto, a newspaper publisher and early JACL leader, to how redress went from a controversial notion to the front burner of the organization’s agenda.

Kamei was also cognizant, however, of the contributions by other community organizations and efforts made toward the eventual success of the redress movement, in particular NCRR (which at the time was known as the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations), NCJAR (National Council for Japanese American Redress) and the three coram nobis cases of Gordon Hirabayashi, Fred Korematsu and Minoru Yasui.

As noted, “When Can We Go Back to America?” begins with Japan’s Dec. 7, 1941, attack in Hawaii. That was followed a little more than two months later by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942. Then, more than 46 years later, came President Ronald Reagan’s signature on the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 on Aug. 10 of that year.

An epic saga would, of course, ensue in between (and after) those bookends of 1942 and 1988; related in Kamei’s book are:

- The mass removal and incarceration in several government-run concentration camps and prisons of some 120,000 ethnic Japanese (including Japanese immigrants then ineligible to become naturalized U.S. citizens, as well as the overwhelming remainder of Japanese Americans who were U.S. citizens) from the West Coast;

- The valiant military service and righteous incarceree resistance;

- Resettlement and reintegration of Japanese Americans from the camps;

- The birth of newer generations of Japanese Americans; and

- The rocky genesis and eventual apotheosis of the drive that saw many individuals and community groups eventually coalesce around the concept of pursuing the constitutional right “to petition the Government for a redress of grievances” that resulted in the federal government admitting that a grave, un-American mistake had been made, complete with an official apology and monetary compensation.

Part of Kamei’s research involved talking with her father about his experiences. In some ways, Hiroshi Kamei was the stereotypical Nisei who didn’t discuss with his children the deprivations of living in a WRA camp nor his family’s plight after their release.

When, however, she was in college and discussions within the JA community over what would later come to be known as redress began to pique her interest, she clearly remembers her father finally opening up about his experiences and then encouraging her to pursue redress.

“This was something that I think was a very special bond with my father,” Kamei said.

“One day, he just started telling me the kinds of challenges that his family faced. They were destitute. They had lost everything.

“He said we didn’t have any ability to get any help or advice,” she continued. “We couldn’t have afforded an attorney, even if we could knew one,” he told her. Within a few years, Susan Kamei would earn a law degree and put that training to use with redress.

Kamei’s research took her to the National Archives in Washington, D.C., and she came across the types of documents she had heard about. She even found papers once touched by her relatives and in-laws. “I was able to appreciate what I was looking at in the files,” she said.

With the book now a reality, Kamei has already begun the process of publicizing “When Can We Go Back to America?” For instance, the Japanese American National Museum has a members-only meet-and-greet event set for Sept. 25 from 1-1:45 p.m. The Simon & Schuster publicity team, meantime, is also working to book her as a guest on public affairs programs.

In 2021, when the issue of reparations for African Americans who still encounter social, economic and educational obstacles more than 15 decades after slavery ended seems to have finally found purchase in the national discourse, not to mention the “Muslim ban” proposed by the previous occupant of the White House, the lessons contained within “When Can We Go Back to America?” are particularly insightful and impactful.

Whether the topic is the history of the Japanese American redress campaign or the nascent African American reparations movement, for Kamei, it comes down to a question: “Why should I care?”

“To answer the question ‘Why should I care?’ is to give these kinds of personal stories that people not of the community can relate to. There are still people walking around today that say, ‘Why shouldn’t we have put these people into camp? They were the enemy.’” Kamei’s book is an attempt to educate all people, but young people in particular, about the reality of what happened in America not so long ago.

Note: The Pacific Citizen is holding a random drawing to give away two copies of “When Can We Go Back to America?” To enter, mail a letter to: Pacific Citizen, ATTN: “When Can We Go Back to America?” 123 Astronaut Ellison S. Onizuka St., Ste. 313, Los Angeles, CA 90012-1767. Letters must be postmarked by Sept 30, 2021. The winners are requested to write a letter to the editor giving their thoughts on the book.

In Orange County, Kamei Legacy Lingers

Like a character out of a Horatio Alger Jr. novel, Hiroshi Kamei, who died in 2007, rose from humble beginnings as a son of Issei tenant farmers in Orange County to, after incarceration and a stint in the Army that sent him to occupied Japan, earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Caltech, followed by a long career in Southern California’s aerospace industry.

Not only an inspiration for Susan and her three younger brothers, Robert, Alan and John, Hiroshi Kamei, who served three terms as the president of the JACL’s SELANOCO chapter, likewise inspired fellow SELANOCO chapter leader Ken Inouye.

Hiroshi and Tami Kamei (Photo: Courtesy of Susan Kamei)

“Hiroshi was a part of helping to found nearly every major Japanese American club in Orange County,” Inouye said. “When there was a need, he was there to help fill the need. In addition, he was one of the individuals in Orange County that helped to educate the people about redress and what happened to Japanese Americans in Orange County.

“Hiroshi was also a very strong mentor to young people,” Inouye continued. “In fact, it was under his leadership and Clarence Nishizu that the SELANOCO chapter decided that it didn’t want to have any more Nisei presidents. … Not only did they pass on the power, they gave all the support that they could.

“I was very lucky to have his counsel over a period of more than two decades. He didn’t try to tell you what to do, but you always looked to him for advice. He was a very soft-spoken man, but he always spoke with a lot of wisdom,” he concluded.

Inouye also had praise for Hiroshi Kamei’s widow, Tami. “She supported Hiroshi in everything he did,” he said. “With Hiroshi’s passing, a lot of us have gotten to know her as well. It’s no surprise that their children are people of great accomplishment.”

— G.T.J.