The much-honored documentary still packs a wallop.

By P.C. Staff

Within a year of the June 23, 1983, death of Vincent Chin at a Detroit hospital after having been pummeled in the head several times by a baseball bat wielded by Ronald Ebens as his stepson, Michael Nitz, held Chin down, filmmakers Christine Choy and Renee Tajima-Peña were already at work. (See related story here.)

Vincent Chin when he was a young man with a bright future awaiting him.

Their project? A critical landmark, a documentary by Asian Americans about the fateful intersection of the lives — and one death — of three men; the city in which they had lived; the automotive industry in which they had found employment; a nation locked in an economic sumo match with another, based not in Europe but in Asia; an emotionally and spiritually broken mother; the violence-spawned birth of a pan-Asian American movement for equal justice; and the legal system through which the dead man’s family and supporters would seek justice.

The name of that project, which would see the light of day in 1987, was “Who Killed Vincent Chin?”

The 82-minute-long documentary would go on to receive an Academy Award nomination in the feature documentary category and win many honors from several other august organizations.

In late 2021, the Library of Congress chose “Who Killed Vincent Chin?” as one of 25 films selected annually for inclusion in its National Film Registry to be preserved for future generations. Furthermore, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Film Archive also recently chose it to be restored.

On June 20, the restored and still-relevant “Who Killed Vincent Chin?” returned to the PBS airwaves on its series “POV” in an encore rebroadcast, more than 30 years after its original airdate, supplemented by new interviews with many of the principals involved in the making of the documentary and the justice for Vincent Chin movement. (It is scheduled to air again on July 16; check your local listings.)

Nearly 40 years ago, “Who Killed Vincent Chin?” which she also co-directed, was the first major film project for Tajima-Peña. To use sports to analogize the situation, it was like she stepped into the batter’s box for the first time and hit not just a homerun but also a grand slam.

Christine Choy (Photo: Sasha Maslov)

But both she and her producing partner and co-director, Christine Choy, had to leap over many hurdles, including what she described as systemic racism, some of which she said still exists now.

“We were really one of the first in public media,” Tajima-Peña told the Pacific Citizen. “The networks never did Asian American stories … Asian Americans would get funding for other projects, maybe you know cultural, things like that, maybe some history stuff.”

She recalled how at the time, someone in the hierarchy decided to give her and Choy a white “overseer” as they worked on “Who Killed Vincent Chin?”

“We weren’t trusted to be impartial and objective — meaning professional — documentary filmmakers, approaching a subject that had to deal with Asian Americans,” said Tajima-Peña. “By the same token, their assumption was a white filmmaker is impartial and objective. … There’s no biological basis for professionalism, so that was really racist.”

Renee Tajima-Peña

In new interviews produced to accompany the rebroadcast of “Who Killed Vincent Chin?” Detroit Public Television senior producer Bill Kubota — himself a documentarian whose credits include “Most Honorable Son,” about WWII tail-gunner Ben Kuroki — learned that one behind-the-scenes person who helped get Choy and Tajima-Peña’s project produced was named Juanita Anderson, who back then worked for WTVS Channel 56, which later became Detroit Public Television.

Kubota says that it was Anderson who recognized that the Chin slaying was not just local in scope but national. She not only recruited the two Asian American filmmakers, but she also helped get the project funding. “She’s like the unsung third person in this project that really made it go,” he said.

Juanita Anderson

Tajima-Peña concurred. “We just lucked out with the DPTV and Juanita Anderson. Juanita at that time was one of the highest-ranking Black women in public media in the country — and you’re talking about only a few Black women in public media. And the president of the station, Bob Larson, also came on as executive producer. Juanita and Bob said, ‘You know, about this overseer guy, we’ll handle him. You just make the film,’” she said. “And that’s the only reason we had the freedom to make what we produced because they stepped in and said, ‘You’ve got to go out and make the film in your own voice.’”

Since that time, Tajima-Peña’s filmography has grown, and she is now a professor of Asian American Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the director for its Center for EthnoCommunications and has an endowed chair in Japanese American Studies. That filmography includes another landmark project that also aired on PBS, the five-hour documentary series “Asian Americans” (May 14, 2020, Pacific Citizen), for which she served as the producer.

Regarding that project, Tajima-Peña revealed how, fast-forwarding nearly 40 years later and with her notable track record, “PBS tried to do the same thing for the ‘Asian American’ series,” she said, referring to how “some suits at PBS” were insisting that, despite her status as the showrunner, they wanted to assign what she described as another “white overseer” who was not only younger but had herself never served as a showrunner.

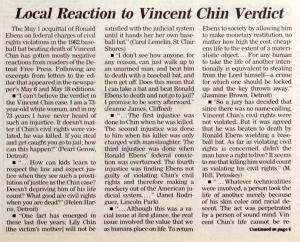

Pacific Citizen coverage of the Vincent Chin verdict from June 5, 1982.

One of the outcomes of the Vincent Chin slaying was the birth of the Detroit-based American Citizens for Justice, which formed organically amongst the then-smaller (compared to now) community of diversified Asian American groups. Active in AJC then and now are Helen Zia, Roland Hwang and James Shimoura.

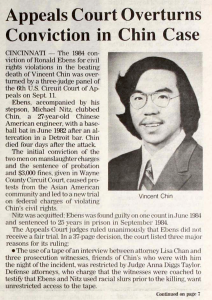

Pacific Citizen coverage of the Vincent Chin case from Sept. 19, 1986.

While Zia’s background was in journalism, Hwang and Shimoura’s profession was law, and both put their legal training to work in the early days of the Vincent Chin legal proceedings.

Shimoura told the Pacific Citizen that in those early days, however, the local press “was not on our side.” He says Zia, however, made contact with a New York Times reporter whose news reporting on the Chin incident put a national spotlight on the case. If not for Zia and the N.Y. Times reporter’s journalism, “I’m not sure where we’d be right now,” he said, referring to the momentum that reporting helped start.

Interestingly and disturbingly, both Hwang and Shimoura separately told the Pacific Citizen that the status quo with regard to anti-Asian violence in 2022 is, from their perspectives, worse now than it was in 1982.

“I think this current situation in 2022 is probably 10 times worse. You had Trump, you know, basically, stoking up white nationalism and nativist alt-right rhetoric about foreigners,” Shimoura said.

“You have a society which I think has more or less validated the ability to attack people, whether you’re Muslim or Asian or Black and blame them for the world’s ills. These last three years, especially since the pandemic hit, I don’t think a day goes by where you don’t have an attack or killing of an Asian in the U.S. somewhere, randomly — and as bad as it was in ’82-’83, we didn’t have an assault of the day. Now, it’s everyday something’s going on.”

As for the importance of “Who Killed Vincent Chin?” being shown again nationally to mark the 40th anniversary of Chin’s death, Kubota said, “I think it remains surprising how many people don’t know about this case. While it rallied all the Asian American groups around here, it’s kind of faded into the past for the rest of the population. … This is a big chance to reach the folks through news coverage again.”